|

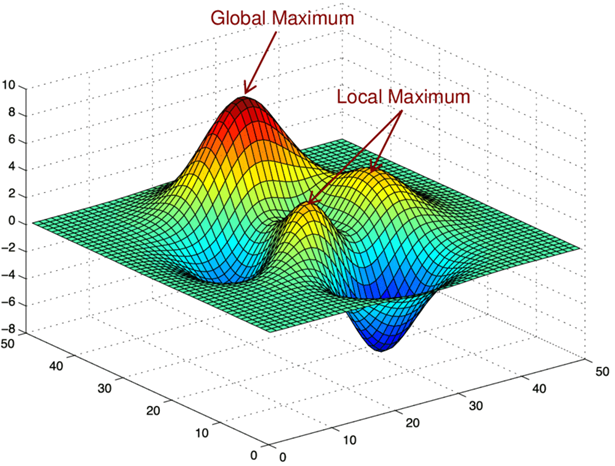

RN: Wole, first of all, I want to tell you how much I enjoyed “An Arc of Electric Skin” – this is a story rich with so many of the elements that make SF such a powerful genre for exploring our condition, and it’s a pleasure to explore it here on Better Dreaming. I think this discussion will also make for a fitting end to this series of explorations of science fiction. So thank you for being the last – the ultimate – conversation in the Better Dreaming series. Reading this story, and considering how to approach it for Better Dreaming, I thought of Samuel Delany’s famous example of how science fiction differs from mainstream (or as he termed it, “mundane” fiction. I’ll quote him here: "'Then her world exploded.' If you say that in a piece of naturalistic fiction, then it's a metaphor for the emotional state of one of the female characters. However, if say that in a piece of science fiction, it might actually mean that a planet, belonging to a woman, blew up." The takeaway for me here was always that science fiction provides a space for metaphors that could not otherwise be used, and also provides a space for the literalization of metaphors, and for the literalization of emotional states. A “wider range of possible meanings” as Delany puts it. And before we continue, I’ll remind readers that there will be spoilers: Better Dreaming talks about entire stories, not parts of stories. The literalization of a state that is both emotional and political is very much an element of “An Arc of Electric Skin”, as I read it. This is a story about a man who gains the ability, through the altering of his skin’s structure, to harness and direct electricity with great violence to destroy a political system that has become unbearable. In an excellent line Akachi Nwosu says: “This country happens to all of us . . . some of us more than others.” Can you tell us a bit about how you think science fiction and its affordances allowed you to tell this kind of tale so effectively? WT: Thank you very much, Ray. I’m glad you enjoyed the story and that it’s the subject of the ultimate story on Better Dreaming. I’ve really enjoyed reading and learning from your deep dives into stories through talking with other authors and I hope there will be more, and perhaps better Better Dreaming to come at some point in the future. Yes, the core of this story is about the literalization of emotional and political states the use of skin as metaphor. To quote from it: “He endured… all of this under the blistering heat of the Lagos sun, increasing his already-high melanin levels, his darkening another physical marker of his endurance. And still, he persisted…” I think that is because that’s exactly how the story came to me. I’d read an interesting paper in the Frontiers in Chemistry journal about the use of heat treatment to increase the conductivity of melanin, which I found fascinating and given that melanin (or eumelanin) is a chemical component of skin, I wondered if there would ever be a way to apply the process to the melanin in human skin, assuming someone could even survive it. I just knew that even if it was theoretically possible, it would have to be painful. And then in October 2020, millions of young Nigerians took to the streets and the internet to protest. The #EndSARS movement quickly blew up but on 20 October, the government sent the army to a protest site at the Lekki tollgate where they opened fire and killed several people. Being Nigerian involves a lot of needless pain, much of which leaves you feeling angry and helpless. I’ve felt that way off and on for a long time since I was a teenager and despite being out of the country, this story, reminded me of all that. And so, this story of Akachi being willing to endure a great amount of pain to gain power to strike back against a government determined to crush its own people came to me. The story in a sense is a literalization of what I knew was the emotional state of many of my fellow Nigerians on the ground back home and I wrote it mostly for them. Science fiction is unique in being a framework that allowed me to do this because of its nature as being both removed from clearly defined reality while simultaneously allowing deeper immersion in a specific aspect of the human experience. As the excellent guidelines for submissions to Asimov’s (where this story first appeared) say: “… consider that all fiction is written to examine or illuminate some aspect of human existence, but that in science fiction the backdrop you work against is the size of the Universe.” This capacity for “removal” from reality, I think, allows the author (and the reader) a certain distance and perspective from exaggeration that can make things more universal, while still retaining enough specificity for the core theme or emotion or philosophical idea to resonate deeply. I think of it as a kind of thought experiment or a mathematical transform. Sometimes an equation is too complex (or cumbersome) to solve in a standard way, but by applying a transform, manipulating it in such a way that some key feature or variable is emphasized, more clearly/simply defined, then it makes it easier to solve. I think of science fiction as being a set of transforms for character and theme elements, for literalizing them. I think if I’d written a similar story about a political action in Nigeria, it might be too personal and painful for me to work through, or for others, or it might not be as impactful, or it might be taken as a kind of propaganda or get lost in the weeds about specific details and historical accuracy when what matters is the feeling and in a sense, directly connecting that feeling of pain and powerlessness and all its varied history, to the power that we possess to change things, difficult as that may be. RN: My second question will be simple, but I have a feeling your answer will not be: why electricity? WT: Surprise! My answer is simple, I think. Its because of the paper linking melanin and conductivity which I mentioned earlier. The ability to control electricity is a common superhero power archetype and this story also plays with the superhero story form. So, conductivity (and consequently the ability to manipulate electricity) lent itself quite smoothly to the idea someone looking for the power to change a system, to longer feel helpless. I did become a bit hand-wavy with the science of how manipulating electricity would actually work but I was more focused on the theme and emotion than going for 100% scientific accuracy. Besides, there is a long tradition of science fiction-adjacent origin stories for superheroes that don’t really hold up to scrutiny. Gamma rays? Lightning? Radioactive Spiders? Sure. Why not add my bio-annealing to the list. Besides, electricity also harkens a bit to the common Nigerian saying “thunder fire you” which implies that lightning (or thunder as we say) would strike down those who did evil as divine retribution, so that was a fun association. RN: I definitely came away with the sense of a superhero origin story but saturated in the realities of place and time and political structure. And I’d like to dig a bit deeper into what you say above about playing with the superhero form. It seems to be a trend recently to make attempts to turn or deepen the superhero mythos. It’s not particularly new – Watchmen was 1986, and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns graphic novel by Frank Miller was definitely an early precursor of the general trend. The Dark Knight novel was over 35 years ago now (can that be true?) but certainly The Boys and Invincible are just two current examples of how this tendency to add grit, and to question the motives and the legitimacy of superheroes, has become a new trope. But while there’s been a lot done to add nuance, the setting hasn’t altered that much: if the stories don’t take place in the United States, they take place in a world that is depicted from the POV of the United States, with few exceptions: versions of Europe, the Middle East, East Asia, and Africa remain very much American (Hollywood) versions of those places that people who have spent any time living in them would find laughable. Here you truly move the superhero setting to a new context, and that brings the story real strength. I personally, as someone who has spent almost half my life outside of the U.S., am hoping for a future for Science Fiction that will be truly global – though we are not nearly there yet. What do you think has to be changed in the way SF is not to make this global future a reality? WT: Yes. I absolutely love the deepening and deconstruction of superheroes because it takes these simplified ideals and attempts to engage with what they really mean and why we are drawn to them. About the “Hollywood” version of places in superhero cinema, I cringe every time the MCU mentions Lagos (where a key incident during Captain America: Civil War takes place). Not only are the depictions of the place and people largely inaccurate, but they also don’t even pronounce the name of the city correctly. I think it goes to show how the place is used as little more than a veneer for diversity, to create the image of ‘globality’, without actually engaging with the place or the people. I was recently on a virtual panel at the 2022 Worldcon called “The Future of Science Fiction Is International” and we talked quite a bit about making SF truly global. I’ll start by saying that making SF global isn’t just about “diversity” or “representation” at a surface level to make people feel good, even though that itself is already a very worthwhile goal (and a natural result). I’d argue that making SF more global is about making SF itself fundamentally better because speculative fiction, especially science fiction as we noted earlier, is a genre of ideas, of concepts, of ways of looking at the world and of being human, so the more of that we are aware of and consider in SF - the more views, philosophies, scientific approaches, religions and cultures, etc. – the more variations of ways of being human that we can factor into our considerations, our stories and our projections about the future of humanity. Producing and reading global science fiction helps us understand ourselves and each other better, it helps us build a better empathy, gives us a broader palette of root ideas to apply to our visions of the future rather than focusing on one dominant hegemonic thought framework. So, anyone that cares about the soul of science fiction should care about its global diversity. To use another mathematics analogy: if you start from only one point or one approach to iteratively solve a complex problem and focus only on it, you can get trapped in what’s called a “local optimum” - where you make progress up to a point and once you ‘peak’, you think that’s the best solution simply because you aren’t aware of the complete problem space or of other starting points and approaches. To arrive at a true ‘global optimum’ (if one exists) usually requires many different starting points, and sometimes different approaches. WT: So how do we get toward a global optimum Science Fiction? I’m not sure but I think there are 3 angles to come at it from simultaneously:

Production: The first step I think is recognizing that people of every society have hopes, fears and dreams about the future, about different ways of being human. And many of them write about it. Or at least would if they could. But not everyone everywhere has the resources, infrastructure and industry in place to do so, or to even reach a local, not to speak of the wider global SF audience. This is at its heart a socio-economic issue, but collaborations can help us trend in the right direction. So for those of us who have access to more resources can reach out and suport local production and translation of SF. For example, the great work that Neil Clarke is doing at Clarkesworld, the consistently excellent work of the folks at Strange Horizons as well as Francesco Verso with Future Fiction. Content: The second and easiest one, I think, is to create better, more global stories. To clarify, I don’t think having global science fiction means that every story should try to include every culture and country and thought and viewpoint and blend them into some weird, thin, homogenous soup. That will probably lead to bad stories that no one wants, not even the authors. Instead, I think we should aim to have a broad body of science fiction that comes from as many places as possible (related to the point above), which while being composed of individual, culturally attuned stories, maintains an awareness of the wider world and its variety of viewpoints/experiences on the core theme of what the story is exploring so that where the story intersects with those other places/people/cultures, it can do so meaningfully, even if briefly. Those are the types of stories that all of us can try to start writing today. For example, Kim Stanley Robinsons The Ministry For The Future is a novel about climate change – a global issue and in it, he shows a keen awareness of the variety of peoples from everywhere in the world and their possible responses to it, while still keeping the story focused on his two main “Western” characters. Reception/Community: This is related more to how works are received after the fact, once they are out in the world. The way we think about what is worthy of recognition and remembrance. For example, Suyi Davies Okungbowa on that panel said something to the effect of: a truly global SFF canon will have multiple entry and exit points or multiple references/touch points for the same things/tropes. I love this as it’s a way to thinking of canon that recognizes that depending on where you’re from you may have come to the same point via different roads or resonated with a different works along the way. So if someone asks for a classic SF “first contact” story, instead of only and always mentioning H.G. Well’s War of the Worlds, we make efforts to also mention Jean-Louis Njemba Medou’s Nnanga Kon, or Lao She’s Cat Country or similar stories. A lot of this can be addressed by reading, critiqing, researching and nominating for awards widely as well as ensuring that when we talk of global science fiction events and community, we try to include as much of the actual world as possible (I’ll note here that Worldcon has been improving at this recently and I hope that continues.) RN: I love this statement you made above: “I think of it as a kind of thought experiment or a mathematical transform. Sometimes an equation is too complex to solve in a certain way but by applying a transform, manipulating it in such a way that some feature or variable is emphasized, more clearly seen, then it makes it easier to solve. I think of science fiction as being a set of transforms for character and them elements, for literalizing them.” It’s a great metaphor for how SF works. Can you talk about how you became drawn to writing science fiction in the first place – your specific pathway into the genre? Was it where you started as a writer, or something you came to later? And why? WT: Thanks Ray. I like mathematical metaphors a lot, as you can probably tell. I suppose one could say I was genetically predisposed to be a science fiction writer because my mother studied English literature and my father studied engineering. It’s a joke I’ve made before. But I think it’s at least partially true because I became drawn to science fiction by reading my parents books when I was very young. I read a lot. Read my dad’s entire encyclopedia collection from A to Z even though I didn’t understand most of it. I read Cyprian Ekwensi and Florence Nwapa. Even Enid Blyton. I remember reading Isaac Asimov’s Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, which charted the history of science from ancient to modern times with short biographies of everyone in it and he tried to make it global, as he could anyway, including some historical Arab and Chinese natural philosophers, etc. And the biographies were wildly entertaining. That had an influence on me. I really enjoyed seeing science and technology not only as topics to study but as things linked to stories of real, relatable people. I was always a reader and eventually, in my teens I started trying to write too. I just liked stories. I didn’t take writing seriously till about 2009 or so though. And while I started out writing all sorts of fiction, mostly published in local Nigerian magazines and online blogs, I naturally drifted back to science fiction (and fantasy) since I’ve always enjoyed those kinds of stories the most. I’ve discussed a bit more of my writing journey in detail in an interview with Geoff Ryman over at Strange Horizons if you or your readers want to know more but that’s the big overview. RN: I love what you say above: “Producing and reading global science fiction helps us understand ourselves and each other better, it helps us build a better empathy, gives us a broader palette of root ideas to apply to our visions of the future rather than focusing on one dominant hegemonic thought framework.” – having lived nearly two decades outside of the United States, I have been struck by how every year it seems more and more local culture is drowned in the slurry of global monoculture. English has become much more of a Lingua Franca than Latin (or certainly the Sabir pidgin, to which the term Lingua Franca actually refers) ever was, and if folk music is passed down from one generation to another these days, it seems it is passed only in the thinnest and most stereotyped of forms, autotuned to death and drowned in imitative studio beats or in a generic pseudo-“Eastern” rhythm. Yet the maintenance of what one might call our “separateness” – the things which make our cultures unique – seems both impossible and, perhaps, not something to be strived for. I worry, at times, that by the time we come to understand one another there will be nothing different left, or only superficial differences left, to understand. Coincidentally, in my real job I have been having conversations with Indigenous people about local ownership and Co-management of parklands, and one of the things they noted is the use of the word “incorporate” as in “Science should learn to incorporate local knowledge into its frameworks.” One of my Indigenous colleagues pointed out that this implies a massive power imbalance, in which science essentially consumes local knowledges (the plural here in intentional) but its own structure does not fundamentally change. I find myself thinking of how rock music in the sixties “incorporated” the sitar and other “Eastern” instrumentation, without fundamentally altering its own DNA. I’ve been pondering this for a while, and trying to come up with a better metaphor for how this relationship should be defined. You outline pathways above – production, content, reception / community – for a more global science fiction. But here is my question: can we keep science fiction from “incorporating” local viewpoints, and instead fundamentally change what it is? And what do you think the best metaphor for the new structure of understanding would be? WT: That’s a great question Ray, a great one. I think we need to go back to the source. “Modern science” as it stands today, took shape in the 19th century, and evolved from natural philosophy before it fully became an empirical framework. So, at its heart science is philosophy. And philosophy is the systematic study of the world. Of existence. Of reality. Every culture has that. However, as you said, I also think that separateness, uniqueness is impossible to maintain. No culture is static anyway. That includes their philosophy. And so, it stands to reason that as cultures and ideas and ways of being encounter each other, they will change, some aspects are lost, modified, improved, and that is inevitable. However, what we would hope is the result of that change is something better than what came before. Something that takes the best elements of both that works for as many people as possible or in appropriate contexts and then moves forward. Which cannot happen when we have a power imbalance as you mentioned. That’s where I think the understanding of science as philosophy can help. I still hear people say things like “Colonization was bad but at least it spread civilization around the world”. And besides the obvious wrongness of that statement, I usually ask them to imagine what the world would be like today if instead of forcibly subjugating and exploiting people they encountered, the colonists had meaningfully engaged with the people and exchanged ideas and understanding of the world equitably. Engaged with the natural philosophies they encountered to move forward together. Imagine what that world could be today if that had been our history. My forthcoming story A Dream of Electric Mothers in the Africa Risen anthology does this. Reimagines an Africa that was never colonized and where local Ifa practices and knowledge has merged with western computer technology to create a different kind of artificial intelligence. But as anyone who’s ever worked in a team can probably attest to, it’s harder and more frustrating to try to truly communicate with people and take everyone’s ideas and thoughts in a balanced way to come up with the best course of action for the team but also far more rewarding when it works. Unfortunately, it’s often easier for the most dominant personality to push their own ideas forward and not let others speak. And while that may get a result faster, its probably not going to be the best result or even a good one but because it keeps getting pushed it seems to be the only way. That’s what I think has been happening for much of human history. Cultures have always been changing but doing so sub-optimally. Sadly, perhaps this is just human nature, that whoever has a perceived power advantage will exploit it. But I choose to believe we can be better than that. I’ve seen enough examples of people coming together with the single objective of finding the best way to resolve an issue to give me faith. So, what can we do as science fiction writers? What I mentioned earlier about production and content and reception of global works is the first step towards establishing a power balance in the field, and hopefully that inspires scientists to seek that balance in their work. At the same time, I think instead of science fiction writers simply reproducing tropes of what “science and technology is” in our fiction, we can try to go back to their core and reimagine the philosophical underpinnings of science and technology before extrapolating them into fiction. Not all the time of course, but enough for it to matter. Imagining a better, different way of science to tell science fiction stories. It’s like alternate history science fiction or even “science fiction of science fiction”. Exciting to think about, isn’t it? RN: It really is, Wole. It really is. And I have a feeling that this is what the best SF is doing, right now. And it is likely the SF of the future. I certainly hope so. I love what you said above about imagining “what the world would be like today if instead of forcibly subjugating and exploiting people they encountered, the colonists had meaningfully engaged with the people and exchanged ideas and understanding of the world equitably. Engaged with the natural philosophies they encountered to move forward together. Imagine what that world could be today if that had been our history.” I think that exercise in uchronia you outline above is an important one. Imagine what we could have been – and could be in the future – if the focus was changed to exchange on equal footing, to cooperation, to open dialogue and learning. What a fitting place to leave this conversation, Wole – and a fitting place to end this cycle of Better Dreaming conversations, of which this is the last for now. It has truly been a joy, and a deeply affecting learning experience, for me to be a part of this. I thank you, Wole, for taking the time to be a part of it as well. I’ve learned a lot from our conversation. WT: And thank you Ray, for the wonderful questions. I really do enjoy deep engagements like this with science fiction work (mine and that of others) so this has been a lot of fun. I’ve learned a lot from your questions, and from Better Dreaming overall. I look forward to learning a lot from the Mountain in the Sea as well. Good luck with the novel. So long (for now), and thanks for all the fish.

1 Comment

|