Mutability

By Ray Nayler

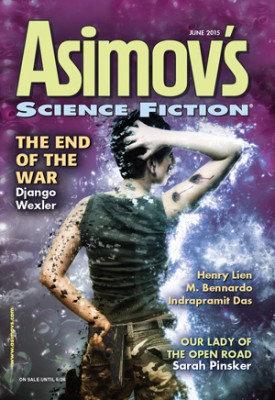

First Published in Asimov's, June 2015

Published in The Year's Best Science Fiction and Fantasy 2016.

We are as clouds that veil the midnight moon;

How restlessly they speed, and gleam, and quiver,

Streaking the darkness radiantly!—yet soon

Night closes round, and they are lost forever:

--Percy Bysshe Shelley

It was an almost perfect café. It was in a red brick building built sometime in the early twentieth century: a mass of art deco, faux-Moorish and Russian influences, punctuated with stained glass and onion-domes. You entered through an Arabian Nights archway into an anteroom of cracked hexagonal tiles and robin’s-egg plaster. Here, you could take off your coat and hang it on one of the brass hooks along the right-hand wall. Turn left through another arch – this one crawling with chipped plaster grapevines – and you were in the main room. This room had a domed ceiling like a mosque or a Turkish bath house, blue Byzantine tiles on the floor, and layers of crumbling posters on the walls interspersed with framed pictures and notes signed by customers. The age-spotted mirrors and dusty bottles of an ancient, hand-carved bar dominated one side of the room.

The bar was where the owner was always to be found, rubbing his shaved head, staring at a game of chess. He always played against one of three different opponents. Opponent One was a gaunt man in a dirty collared shirt who chewed, repulsively, on a piece of string hanging from the corner of his mouth. Opponent Two was a heavy, slope-shouldered man. He kept his coat on and played quickly and impatiently. Opponent Three was a girl, thirteen or so, with a nose she was trying to grow into and blonde hair that looked like it had been rubbed in ashes. One so rarely saw children these days. Very serious, she always came in with a book – a real book. Where was she getting them?

It was unclear who won any of the long, silent games. Once they were over, Opponent One or Opponent Two would get up and leave, with no hint of triumph or desolation. Opponent Three would stay and read her book for hours, accepting the occasional cocoa on the counter nearby while the owner busied himself with other things. His child? Who knew? The owner never spoke to the café’s customers, with the exception of these three.

The rest of the room was filled with tables, chairs, and light. The tables were an assortment of round café tables, square or rectangular tables from restaurants or offices long since gone, high tile-topped wrought-iron tables of the kind you might find in a garden or on a balcony somewhere, big scarred oaken slabs that might have come from a warehouse or factory. The chairs were also a mix: some straight-backed, some cane, some wicker, some just plain stools. All were defective in their unique way, and all demanded different techniques for getting comfortable. The chairs and tables were never to be found in quite the same configuration when Sebastian came in in the mornings. The light was never in the same configuration either: it fell piebald through the stained glass panels at the top of the windows in a moody shift along the tiles and tables and chairs, dependent on cloud and season.

And so the café had the feeling, at once, of agelessness—its ancient building, its collection of rescued furniture like a museum of other places, its continual game of chess in the corner—and of change: the patterns of color-stained light and the restless puzzle of tables and chairs. All this, and the coffee, sandwiches, and macaroons were excellent. All this, and the service was good.

But what made it nearly perfect was Sebastian’s place in the corner, against the wall furthest from the entrance, by the windows. Here there was an enormous, worn, purple-velvet armchair and a massive oak table. There was enough room on that ancient table to spread his work out; the terminal and the notebooks he liked to use when he wanted the mechanical action of writing by hand, the cup of coffee brought steaming to the table by one of the students from the nearby universities who worked here (they were like the light and the chairs and tables, moving always elsewhere). The waiters never came around to ask if he wanted anything else, but they were always near the bar, scanning the customers for a motion that meant something was needed, that meant it was time for the check.

He had found the café at a terrible time in his life. He felt, in a way, as though the café had saved him. The long days of work, or of just watching the light slide across the floor, or just watching other customers—in hushed conversation, or bent over their terminals, or just staring off at nothing – made him feel a quiet part of something. He was welcome here. He was known, but left alone. He could work here in a way he could never work at home. At home, when he tried to attack a particularly difficult problem in the work, something would distract him. Hours later he would find himself staring blankly into his terminal, reading about god knows what insignificant detail of research on something completely unrelated to what he had been looking for. Here, surrounded by pleasant, human-scale distractions, he found his focus.

Sebastian had noticed her long before she approached him. More exactly, he had noticed her notice him. He’d looked up and caught her staring at him. Later he would examine the moment: rain outside that the wind occasionally drove against the windows, streaking through the dust in alluvial fans toward the bottom of the glass. A special feeling of refuge in the café that day. The smell that the rain brought in along with new customers seeking shelter—one of which was this tall, dark-haired woman in a gray dress and moss-green scarf. It was a hard, autumn rain that said winter was coming, a rain that drove the loosening gold leaves from their branches to the ground. He had not seen her before, and he caught her looking at him—really looking at him, in a way at once rude and mystifying. She looked away when he looked up, but he was aware of her glancing at him while he worked. The rain hammered the streets and the buildings outside and the place filled up with more dripping refugees. When he came home that evening, the maple in the courtyard, which that morning had been wrapped in red and yellow, was a winter skeleton.

The next day she was there early. She stayed most of the day, with a terminal for company. Also the day after. On the fourth day she stopped him in the anteroom. Outside, the evening street was shadow-colored. Above the buildings, the flushed undersides of clouds were dark blue and salmon. He was lifting his ancient shooting jacket from a hook. She came in, reached for a threadbare pea coat. Then she stopped, resting her hand on the collar of her coat, and turned to him.

“I have a strange request.”

He had the jacket on and was shifting it to fall correctly over his shoulders. There was a little whirring blade of cold air in the anteroom, and it nipped at his wrists and climbed up his pant leg. The world, hesitating between fall and winter, all brown dry leaves and flights of migrating birds headed south. “How strange is it?”

She had small crows’ feet around her eyes, a vertical worry-line between her high, dark eyebrows. Longish hands, unpainted fingernails cut short. She could have been a musician, or many other things.

“I live near here. I wonder if you would come to my apartment so I can show you something.”

What did he read in her face? Impossible to say. There should be a class offered in reading the expressions of others. Perhaps there already was: he would ask his terminal. “All right. Now, you mean?”

“If it’s not too much trouble.” She began, quite clumsily, to put on her coat, dropping mossy scarf and grey gloves on the floor in the process. He picked them up for her, handed them back. She carefully avoided touching him when he did so. The impossibilities of reading other people. Were some people able to do so? He thought yes, certainly better than he. They went out into the cold street.

Her apartment was on the next block – but because the apartment buildings (most of them in this section of town very ancient) were enormously long, it was a 10 minute walk. The days were shortening, and the chill filled him with positive melancholy: winter was hot drinks and flushed cheeks and good books. Leaves scuttled across the pavement. Overhead, the dark spider web of the Nanocarbon Elevated Metro (NEM) striped black through the indigo air, a train doppling past. For some reason, they did not speak much. She was tense. She seemed to be working herself up to something. She did tell him her name: Sophia.

Her apartment was on the third floor of an unobtrusively upgraded old building. The lack of draftiness inside was probably due to insulating nanofiber injections into the walls. The modern voice/ret scanner near the entrance to her stairwell posing as an antiquated domofon. The dismal authenticity of the concrete stairwell had been maintained. The apartment was high-ceilinged but small, just one rectangular room furnished with a matroshka furniture cluster, which she converted with a touch to its table and chairs format. A kitchenette near the windows overlooked the street. Refrigerator unit, old-fashioned tea kettle, instantheat, a cabinet from which she drew two mugs and a teapot. While she was making the tea he politely scanned the room. Besides the matroshka unit, a bookshelf along one wall held a selection of music theory books, two terminals not of the latest make, a violin, and a shelf of carefully collected, vintage psychoanalytical works – not first editions, but well-known translations. On the opposite wall, a painting in which several female forms dissolved in a grey and red-streaked fog. Difficult to place its period: eccentric and not of any particular school, artist likely an unknown, but fantastically talented: the piece moved him. He looked away from it.

Sophia set the two mugs and the teapot on the table. The apartment was full, now, of the scent of the steeping tea, black with some sort of berry in it. The window near the electric kettle was obscured by steam: the other windows mirrored the room, and Sebastian and Sophie standing in the room. He sat down on the backless cube of a chair. She poured him tea. He looked up to find her deep in thought, staring hard into his face. She caught herself and looked away.

“You must think I’m very strange,” she said.

Sebastian stared into his tea. Miniature leaves floated, unfolding in the heat of the water. “Who isn’t, these days?”

She was holding an envelope in her left hand. She placed the envelope on the table.

“First of all,” she said – “please take a look at this.”

Sebastian opened the unsealed envelope and drew out a photograph. It was a color photograph, very old. Its tones were shifting toward orange and red as it aged. The edges were yellowed, although it had been printed on supposedly archival paper. It had been badly bent a number of times, and creased once diagonally, then re-straightened. The two people in the photograph were wearing laughably out-of-fashion winter coats: coats that would have been normal now only in some sort of historical drama. They were grinning into the camera. The man was wearing a wool watch cap, the woman a beret. Behind them there were some very neat, tiny houses almost entirely obscured by snow. Judging by the architecture of the houses, the picture was taken somewhere in northern Europe. A very pale light. Very far north. The couple looked truly happy: their arms around one another, their heads leaned in to one another, the crown of the woman’s head against the man’s jaw.

It was a photograph of Sebastian and Sophia. Their hair was significantly different (his was just terrible, unflattering. What could he have been thinking? Hers looked nice). Their clothes of course were different, but there was no doubt at all that it was the two of them. He looked for a long time at the photo, turned it over and looked at its back. Nothing there but the digital printing from the machine – a series of numbers, some kind of internal code from wherever it had been printed, barely legible now. No date, but he could guess by the clothes that it was . . .

“The first thing you think. The first thing that comes to mind.”

He looked up. She was leaning in a bit toward him, both of her hands wrapped around her mug of tea.

“Well . . . it’s us. I mean . . . it appears to be a picture of you and me. But I don’t . . .”

“No, you wouldn’t remember it, Sebastian.” She said his name strangely, like a person afraid to pronounce a word incorrectly that they had only read in books. “I don’t remember it. I don’t remember anything of it. It’s . . .” She stood up suddenly and went to the window. “It’s well beyond my memory horizon. I’ve researched the picture. Looked up the fashion of the clothes. Not . . . obsessively. Just – because I’ve always had it with me. I found it in my things, I think . . . I can’t remember exactly. But this picture . . . which I’ve carried with me as long as I can remember . . . I think it’s about four hundred or so years old. That’s just a guess. It could be three hundred ninety and their – our – clothes are out of style, but it’s probably closer to four hundred. I need to walk. Do you want to go for a walk? I can’t be in here with you.”

They walked along the river embankment. There was no ice yet on the river, but a serpent of freezing air coiled down its length, winding winter into the city. They crossed the river via an escalator and an enclosed pedestrian footbridge. Below, the black mirror of river reflected the city up at them. There were, of course, no stars.

“I don’t know how long ago I found it. I have a vague recollection of pulling it out from the pages of a book. The book is battered:” –she was walking with her eyes shut—“and it has a white cover. With only text on it. Like handwritten text. And green stripes? I remember green stripes. The book is gone now – I can’t recall what I did with it, but it’s been gone a long time. I’ve tried as hard as I could to remember the title of the book, and I can’t.

She stopped walking and turned to him suddenly. “Tell me your oldest memory.”

“Clear or muddled?”

“The oldest one you are sure is not a dream, but an actual memory.”

“Okay . . .” In the distance, down a turn of the river, the sections of a residential skyscraper slowly rotated, changing which of its balconies had a view of the river below. “I’m standing on the deck of a ship. It’s massive – almost the size of a city, and its deck is covered with stacked containers. You know the ones. Apartment containers, with catwalks and gantries between them. I’ve examined the feelings around this memory: I’m at the end, maybe, of a long period of being sad. I look at my hands. I’m holding pieces of something in them. But I can’t see what it is, closely. Whatever it is, it’s mostly white and orange. I can’t identify it for the life of me—I’ve spent hours trying. I open my hands, and the stuff drifts out of them, is caught by the wind, and then falls down along the huge side of the ship and out of sight. And I remember feeling disappointed: I had wanted the drama of seeing it hit the water, but I could not see it. It just – went away under this enormous bulk. Gone.

“The next clear memory is months afterward, and after that they get clearer and clearer of course. That one must have been very strong to have lasted for so long. I sort of keep retelling it to myself. To see if I can remember it. Forever . . .”

“It must have been one of those round-the-world container-home trips.” she said. I remember the ads: ‘Travel around the world for five years, all in the comfort of your own home.’ The whole idea was a bit unwieldy, a lot of diesel fumes and seedy ports, but people signed up who had the time and the tenghe. They were popular for a long time. Until one of those liners went down in the Atlantic, remember?”

“Fifty years ago.”

“Sixty, I think.”

“It could easily be. I keep so little track, these days.” They were on the down escalator, across the river now. Outside, cobblestones and cold. The entire center of the city had been restored to the way it was hundreds and hundreds of years before anyone could possibly remember – even the professional mnemosynes. He liked that about it: it was why he lived here: and also why, he imagined, Sophia lived here. Their gloved hands bumped against one another as Sophia changed direction, leading them up a narrow side street. There were bicycle stations everywhere, of course: no cars allowed within 250 blocks of here. His own bicycle was at a station not so far away. They were within walking distance of his place. He blew through the fabric of his gloves. Time to switch from the fall to the winter pair. He felt a sense of dread opening in him, and he wanted to be away from Sophia and home among his SAE texts, pushing himself through another hour of studying, closed off in that little, specific world. She put a hand on his shoulder as she turned, stopping him, blocking the sidewalk in front of him.

“I’m not a superstitious person, you know.” A gust came off the river and hissed evilly through the dry-leafed trees. They both laughed. “No matter how hard the world tries to make me one. I don’t think I believe in fate or anything else. But I want to say a few things. Can I?”

He blinked. “Why wouldn’t you be able to?”

“Right. What I want to say is: my oldest memory is of finding that picture. And they say – all the books say – that the memories that survive for the longest are the ones that are somehow important. Some even say, the ones that carry some sort of a key inside them to something else. I don’t know if it’s true – but it makes sense that you remember the more important things for longer. That’s one.” She counted it on her glove.

“Two is – we look really happy in that picture, in a way that I know I haven’t felt for as long as I can remember. Which is a long time. And I’m not saying that I haven’t been happy . . . but not like that picture. Nothing like that. Those people . . . we . . . were happy.

“Three is – I’ve kept the picture, but I haven’t been looking for you. Maybe keeping an eye out, half-consciously, but how would I ever find this person in a photo I couldn’t remember taking? Hire a detective? So I just kept it. I was maybe hoping. But not . . . looking. And the picture was taken a long way from here and a long time ago. And the fact that I went into that café – because it was raining, only because it was raining – and saw you there – not looking for you – makes me feel– although I’m pretty terrified of you – that this seems right.”

Standing still was pushing the cold all the way up his thighs. It would be time to switch to long underwear again, as well. “It does. It seems right.”

She started backing up the street. “Okay. Go home, it’s cold. I’ll see you tomorrow.”

He just stood there for a while, after the shadows under the furthest trees had drowned her shape. She was not walking toward her apartment, but further away from it – he wondered how much further. He turned left and went down the embankment, turning details over in his mind and trying to remember things. Did he remember her? Now that he had seen the picture, it seemed as if he did, but he knew the way these false memories could be constructed by the mind: you would remember a moment, but in the memory, you would be looking into your own face, or looking down at yourself from above – which meant it couldn’t possibly be real. And they said that every time you remembered something, you subtly changed the memory to suit the present moment. He had no independent recollection of her. A hoax? There were memory con artists, some of them incredibly skilled; whole volumes had been written on them.

But he felt sure that Sophia was exactly who she seemed to be. It was a stubborn, ignorant sureness, but it was all he had. He walked a long way down the cold, concrete embankment, very much aware of his fragile, warm form along the river bank.

At five in the morning he clambered clumsily out of bed in the dark. He was sweating. He must have been dreaming, but the dream was gone, only the impulse remained. He searched desperately in the dark, not even thinking to turn on the light. It was here, somewhere . . .

Today it was Opponent Three, the little girl. Sebastian was earlier than usual: after waking up at five, he had not been able to sleep. Finally, at seven or so – much earlier than he usually got up, these days – he forced himself into the shower tube, then flung on the old shooting jacket, took his bag, and went out for breakfast to a little Greek place on the corner. For some reason he did not want to go to the café yet. The book on SAE theory was a blur, he kept reading broken bits of sentences, backtracking over whole pages, closing the book and staring out into the quiet, early street. Finally he just got up, leaving the breakfast half finished, and went to the café to wait. It was not a morning café; not the kind of place that people came to for a quick cup of coffee before work, but more the kind of place people just – came to. There was just a smattering of customers reading their terminals, and the owner at the far corner of the bar, playing chess with the serious little girl. At first, Sebastian would be quiet. He would let Sophia talk first – get whatever it was out of her system. Then he would show her. And then what? He couldn’t know. For the first time in a very long time, he was frightened of making a mistake, and he realized that there was something in him, some capacity, like a forgotten function, like an unused piece of programming that he had not used in a long time.

Outside, it started to rain. Not a normal autumn rain, or an early winter rain – but a rain of surprising force. Wind came hammering down the street and awnings flapped, then hail rattled and smacked against the windows. The little girl looked up from the chess game with a look on her face of joy and wonder at the horrible weather – Sebastian’s reaction too, normally. But now the storm threw him into a panic as the rain mixed with sleet, then snow, then freezing rain, and shellacked the windows with distorting ice. Everyone looked around. Customers ordered second cups of coffee. Nobody was worried yet, but nobody was going anywhere. In books in the old days he knew that this was about the time that the power would go out, candles would be brought around, and they would begin to tell stories to one another, or some such thing. The beginning of a one-act play. Of course, the last time there had been a power outage in the city was well beyond anyone’s memory horizon. Still, a few people did look up at one another, acknowledging for the first time that other humans were also in this room. A banner across his terminal announced a temporary reduction of NEM service. The city was in the midst of a major ice storm.

Within two hours, much of the storm had past, without real damage done to anything. The streets were mechanically cleared thirty minutes after that, and the city returned to its normal, subdued level of activity – but Sophia did not come. Sebastian went home in the dark, up streets forested with icicles. It occurred to him that poems, like eucalyptus trees, poisoned the ground beneath them. Eventually, there would be no soil left where anything new could grow. Eventually, there would be no writing about human feeling left to be done at all – only reading.

There was an Opponent Four. This was something new. Sebastian had come in very early. He dropped into his usual place and ordered a macaroon and a Japanese coffee. How long had the place been a café? Longer, possibly, than he had been alive, which was a very long time. He had moved so long from one obsession to another. Now he thought that, underneath all that concentration—all the papers for peer-reviewed journals, all the attention to syntax and SAE peculiarities and dialectical variations—all the careful research, decades of it—was something else. Some sort of breadcrumb trail he hadn’t even been aware of following, leading off into the darkness. In the meantime he had been analyzing, in excruciating detail, the symbolism in the presentation of the contents of a medicine cabinet, the details of a young man shaving in the mid-twentieth century, the typology of Manhattan apartments, haiku in SAE translation, Western appropriations and reinterpretations of Buddhist thought, twentieth century traditions of suicide . . . Simply to justify his existence, he had thought, when he no longer had to work for money because some version of himself that he could not remember had done all the work for him. Only now did he realize what it was he had really been doing.

A bicycle went past, a manual type, as mandated by city ordnance, making a pleasant nostalgic clatter over the cobbled street. Opponent Four was a woman in a nurse’s uniform, but without her hat on, and in regular walking shoes. Just off a night shift? She was standing, bent over the board. A sky-blue wool coat was thrown over barstool next to her, as if she had just swept in off the street and didn’t intend to stay long. “. . . and . . . mate,” She said, clapping her hands together.

“You’re good,” said the owner.

“Well,” said Opponent Four, “I’ve been playing for as long as I can remember.”

The owner rubbed his shaved head. “So have I. A lot of good it’s done me.”

The nurse put her jacket on and turned. Seeing Sebastian in his usual place in the corner, she walked over.

“You’re Sebastian.”

“Yes,” swallowing macaroon. “Yes. Do I know you?”

“Sophie asked me to stop in here and tell you she’s in the hospital. Central District Hospital #2, just up the street. She slipped on the ice yesterday, broke her elbow very badly. Surgery’s tomorrow. Glad I caught you in time.” She turned and walked out.

Sophie looked like she was being eaten, right arm first, by a white, ovoid machine. The machine was suspended over the bed at the end of a multi-jointed armature. A slight green glow spilled from it and across the side of Sophie’s face.

“Latest of the latest,” Sophie said. “Same technology they use in limb re-growth – it’s supposed to shorten healing time by about 95% - I should have full mobility in four days. You brought flowers, which is incredibly antique of you. This thing feels weird.”

He sat on the chair next to the bed. “You have surgery tomorrow?”

She frowned. “No, just more of this. Is that what they told you?”

“The nurse told me.”

“That woman has a very strange sense of humor.”

“What does it feel like?”

“It feels like . . . ants crawling up and down the bones of my arm and massing at my elbow. Crawling through the marrow of my bones. But it doesn’t hurt – it tickles. Very strange. Very unpleasant, without being painful. I’d rather not experience it again. This is all very dramatic – ice storms and broken limbs and messengers.”

“And strange requests in anterooms, and photographs.”

She smiled. “My hair is greasy, and I’ve done nothing with my life for about the last hundred years except diddle around on the violin and pretend to write a book on Freud. I can’t even be bothered to learn German. So . . . embarrassing.”

“Possibly of more use than what I have been up to.”

“Which is?”

“An obsession. I’ve built a minor career around it. In fact, I might be, because of it, the world’s foremost expert on Specific American Englishes of the Period 1950-1964, especially those related to the works of one author.”

“Okay, that rivals my idiotic Freud project. Why?”

“I came across a translation of a book. Maybe it was 60 years ago now. I wasn’t living here at the time, but out East at a cataloguing dig. One of the abandoned cities. Another archaeologist loaned me this old book he had – this was just at the time when the fad for paper books was coming back around. I read it, and read it again, and again. I felt drawn to it. I would read parts of it again and again. And I couldn’t really understand it: the sentences seemed tangled. The book seemed to be about nothing at all, or about something that I couldn’t possibly grasp. But these little glowing pieces that I did understand – they fascinated me. I was sure that it was the translation getting in the way. So I decided I would learn to read it in the original.”

“Why?”

“I wouldn’t have been able to tell you. I thought at the time that it was because I desperately needed something to do. This thing was as good as any other thing. But it’s what I’ve done now for decades. I’ve studied this very particular, dead version of English. It isn’t really that different from the kind they speak nowadays – maybe half the words are the same, maybe more. The grammar has changed, of course. Mostly, the challenge lies in understanding the world they lived in, which is so different from ours. Their world is so shadowed by inevitabilities, especially the inevitability of death, which covers everything. And of course everything moves so urgently. Everything is so compressed. Yet they waste time with a terrible determination, as well. I knew at least a little modern English, so that was a start. After a few years, I began to forget exactly why I had started the project. I’d become fascinated with all of the little details along the way. Complex, endless little problems. And I started to publish in the field, after a while. Then it became about that – about the academic side of it. The very fine distinctions.

“Several years ago, I was digging around in one of the little antique shops here in the city center, and I came across a paperback copy of the book. The same one that had gotten me started. In decent condition – and you know how rare they are these days, though they were very common at the time. It wasn’t a first edition or anything, but it was of the period, in the original language, and it was in decent shape. I honestly thought I would never find one. Before that, I had always worked from my terminal on electronic texts.

“I was so happy – I remember being happier than I had been about anything in – well, in a very long time. I walked down to the park and I read it – in the original – cover to cover. It was dark when I finished. I remember that I sat there for it seemed like hours afterwards, trying to hold on to this—mode—that I had slipped into. A particular shape of the world, a tone to things. Like when someone says ‘it struck a chord’ in me. That must be the rough, dead metaphor for this feeling – but it’s nothing like the thing itself.”

He looked at Sophie. She was staring back at him. The machine on her arm bleeped. She turned her head and scowled at it, “oh, shut up, machine. What do you know?” She turned back to Sebastian. “Keep talking, you.”

“It had taken me fifty-three years to get to that point, where I could read it like that – understand every word, know their world almost as if I had lived in it. I felt like it had all been worth it. And I felt as if I had been following some kind of trail into the dark. I had been following that trail for so long that I had forgotten what I was doing. I had begun to think that I was just walking aimlessly. And then I had come across something that I was looking for. It didn’t feel like the end, the final thing. But it was like . . . a waypoint.

“Then that night, after we talked . . . I didn’t realize it right away. . .”

He reached into his bag and withdrew a paperback book. It was crumpled, curved of spine, and fragile-looking, packaged carefully in a sleeve of clear plastic. There was, unusually, no illustration on the white paper of the cover – only the book’s title and the author’s name, printed to look as if they had been hand-written with a fountain pen, and a pair of green stripes bisecting the cover, about three-quarters of the way down its white surface.

He put it in her good hand. “This,” he said. “I didn’t realize this. It’s the thing that I’ve been studying for all these years. You see? The trail that led off into the dark. The SAE English, the haiku, the contents of a medicine cabinet . . . they all lead here, to a silly little book that shouldn’t have had any meaning for me at all.”

She held the little book in her hand, moving her hand slightly up and down, as if testing the weight of the thing. She turned it over. The back cover was the same as the front cover, except for a bar code near the bottom – the sort of thing not seen a book for three hundred years, at least. The lower corner of the back cover was torn.

“I feel like I’ve seen it before.”

“You have.” He said. “It’s the book you took our picture from. You described it to me. In your apartment. A white cover. Only text on it. Handwritten text. And green stripes. It’s the book you put on a shelf once in a little bookstore, meaning to forget it.”

She set the book down on the bed sheet. Then picked it up again. Then put it down, adjusted it a bit. “Yes. This is it.” She shook her head, closed her eyes for a second. Opened them again. “This is it.”

It was an almost perfect café. It was in a red brick building that turned burgundy in the rain, when the rain streamed down its onion domes and its stained glass. Through the archway of chipped grapevines, under the dome of the main room, stood the old, mirrored bar with its bottles gathering dust and the silvered mirrors growing darker every year.

The bar was where the owner was always to be found, rubbing his shaved head, staring at a game of chess. He always played against one of three different opponents. Opponent One was a nurse who stopped by in her uniform around lunch time. She played quickly, and when she won – as she nearly always did – she clapped her hands together, said “ha!” and walked out. Opponent Two was a woman with a nose she had never quite grown into and blonde hair like ashes. She would finish the game and, win or lose, sink her pointed face into a book, sipping her coffee in silence. Opponent Three was Sebastian. He played slowly and carefully, with a sort of desperate concentration. After three decades he still had not won a game.

The rest of the room was a shifting dance of tables, chairs, and light. The chairs and tables were never in quite the same configuration when Sebastian came in. He suspected that, after the café closed, the owner moved them around, just for the sake of moving them. The light was never the same either: it fell through the stained glass in a moody shift, dependent on cloud and season.

But what made it nearly perfect was the place in the corner, against the wall furthest from the entrance, by the windows. Here there was an enormous, purple-velvet armchair, a battered wicker high-backed chair, and a massive oak table. When he lost, as he always did, Sebastian would cross the room, shaking his head, and settle into the armchair. Sophie would look up at him from her terminal and sigh.

“One day, you’ll give up.”

“One day, I’ll win.”

And so the café had the feeling, at once, of agelessness—its ancient building, its collection of rescued furniture, its continual game of chess in the corner—and of change: the patterns of color-stained light and the dance of tables and chairs. All this, and the macaroons were excellent. All this, and the service was good.