Do Not Forget Me

by Ray Nayler

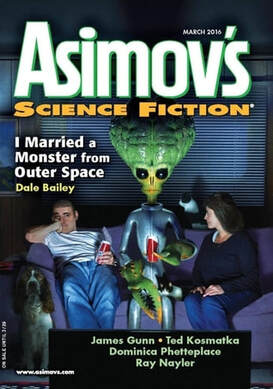

First Published in Asimov's March 2016

What is my true substance?

What will remain of me after my death?

Our life is as short as a raging fire:

flames the passer-by soon forgets,

ashes the wind blows away.

A man's life.

--Omar Khayyam, The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

I: Batyr

When Batyr came into the bedroom, the oil lamps were all lit, as he had hoped they would be. Leila did not greet him. She was playing with him, of course, hiding behind the curtains of their canopied Western-style bed as she often did. Why else would the heavy wool curtains be closed on such a warm spring night? Certainly, she had heard him coming into the courtyard. She had of course heard him take his boots off by the door. Before that, she must have heard the dogs barking as his horse approached the house. She had been waiting up for him, and was now hiding, pretending to be asleep. He lifted a hand to push the bed curtains aside.

Her voice came from behind him. “You are not drunk.”

Batyr turned. Leila stood in the bedroom doorway, wrapped in one of his quilted riding coats, which she had long ago claimed for herself. Her silk nightgown was visible at the throat and the sleeves, which she had folded back to accommodate her shorter arms. She was bare-footed. She had just gone to the kitchen: she held a wooden bowl of dried mulberries in one hand, and in the other a cup of milk.

“No,” he said. “I am not drunk.”

“I had expected you to be drunk: the Great Poet has a reputation to uphold, and I expected you would have to keep up with him.”

“You would be interested to know,” Batyr said, “that the Great Poet also was not drunk. That in fact there was no drinking, except for tea. But I could not possibly eat one more mulberry tonight. I feel like I have been stuffed with mulberries.”

“These are not for you.” Leila bit him on the shoulder as she passed, pushed the curtains apart with a foot, and deftly climbed up onto the high mattress, settling in among the sheets and pillows with her milk and mulberries. She always brought grace and style to the act of eating in bed. “These mulberries are for me to eat while you tell me all about the Great Poet, who you were so excited to meet, and about all the wonderful poems he recited to you. I am sure that, like a dutiful husband, you have memorized the poems so you can recite them to me. I am glad you are not drunk: you will be able to recite better.”

“You know, he is also a great mathematician and astronomer. In fact, I think he is better known for those things.”

Leila grinned at him. Her lips and teeth, he noticed, were already purple with mulberries. She had been eating them on the way back from the kitchen, probably by simply raising the wooden bowl to her face, since her other hand was full. He had seen her do this many times before. “Oh, who cares about that? Do you think I want you to recite some mathematical theory to me? After midnight? Or take me outside and point out all the boring stars where they blink stupidly in the firmament?”

Batyr poked her in the side. “You are terrible, and will keep me up all night.”

“As if you were going to get up with the Muezzin’s first call and pray! If I saw you at first prayer, I would know for certain that some jinn had spirited my true husband away, and I would kill you with a spear.”

On his way back home from the inn, Batyr had fallen into melancholy thoughts. All of this, he had thought as he passed the quiet whitewashed houses on the way—the fields and orchards outside the city wall, will soon enough be gone. A man had passed him traveling in the other direction, wrapped and hooded on a skinny nag. I will be gone, and my Leila. And even if we have our children, and they are happy and have their children, they will soon enough be gone. And where will we go? He wanted to believe in something after this life, but could not. The passing man’s thin, ill-kept horse had disturbed him. The facelessness of the man, a stranger, who did not even turn to greet him, but went silent on his way—as if Batyr were already nothing. And where are we now? What is this place here, which is our only world?

There was nowhere to go with these thoughts. Only the cold feeling and fear. So now he was very glad for the warm light of the oil lamps, and very glad for Leila, who managed to nestle the cup of milk between her knees so she could more easily eat mulberries. This woman was better than him and was the only thing that he would go willingly into darkness for.

“He recited no poetry. And yet he told us something better: a story.”

“Oh, good! That’s even better than a poem. In fact, I have to admit I was not going to listen very closely to a poem. Poems are pretty and pleasing, but boring in the end, like our neighbor’s new daughter in law. Poems are all about the same things. Love and god or war or flowers or the moon.”

Batyr was drawing on his night robe now, folding his clothes and placing them on the chest in the corner. “It was the most extraordinary story I have ever heard in my life, Leila.”

“Then you must not start with the story, but first tell me about the Great Poet and why he did not drink, and what he is really like. And then tell me his story.”

“In fact,” Batyr said, finally coming to bed, “it was not his story, but a story that was told to him. Or at least that is what he said. But it is a true story, though it seems incredible.”

Leila handed him the cup of milk, and he drank from it. Not because he was thirsty, but because he took all that she offered him, without question.

“Good,” she said. “Then we will be up all night, and we will sleep half the day with the courtyard gates locked. Then we will get up and eat everything left over from today in one meal, lay about, play a few games, and go back to sleep. Ahmed and Nooriya have the day off to tend their garden and visit relatives, and nobody will miss us.”

Nothing could be closer to what Batyr wanted. And so he began:

The Great Poet

“When we arrived the Poet was already there, talking with a man that we did not know. He looked to have been there for some time. The sun was not yet down, but the owner of the inn had already lit the lanterns in the grove of willow trees. Of course, the Poet had been given the best place in the gardens, outside under the largest willow tree, on the wooden platform there that leans out above the river. The river is now fast with mountain water, and louder than usual, which made the whole thing strange: we had to sit close to one another and lean in to talk. The Poet’s voice is not a large voice. It is very deep, and like some deep voices, it does not carry well over other sounds. The Poet is an old man, but not like you might imagine: he is a large man, not fat but large through the chest and shoulders, as if he had been built for fighting or plowing rather than for poetry and science, and his hands are square and hard. Some black still runs through his beard, though he must be seventy and more. He carries himself like a man who simply ignores age. I mean to say that he holds himself quite straight, does not walk with a stick, and does not yet seem ill. He has the mountain eyes, of a brown that is green in some lights.

“The man who was with him had a rare name – Turanbek. He was in his middle life, and could have been the Poet’s son, as he was of nearly the same build and had a face that was like the Poet’s. But he was not his son – he was a servant or an apprentice. Several times he stood to go and bring more food or tea to us. He hardly spoke after all of us were introduced. I will not describe him further: he is not important to this tale. Nor are the others who came with me or who joined us, interrupting the Poet’s story to clasp hands and greet him. They are only shadows here, and you should imagine them as just men, with their beards reddish in the light of the lantern and the sun that was now setting. Sometimes they would speak or ask a question, but mostly the Poet spoke. As I said, he was not drunk: he had not drunk, he said, in a good long time. When one of the men asked the Poet where the best wine came from (because the Poet is famous for being very fond of his wine, and as you know much of his verse is about it) he laughed and said that wine is just a metaphor, and who knows where metaphors come from? Likely from God. Everybody laughed, though few understood what he meant. That was all right: he was not the kind of man who makes you feel nervous or uncomfortable when you say something that is not quite right or do not understand him: he is the kind of man who makes you feel you are all together as friends when you are with him. I think he could have been a great leader of men, though this is not what he chose.

“The Poet said that just before he arrived at the inn, he had passed a man walking in the road. The man had looked like another man he knew, many years ago: a man with a rare face, very long and with large ears, like a Greek jug. It was a face you see few men wearing, and so he had thought this man was certainly him. As he grew closer, he could see he was mistaken. But one thing leads to another in the mind, and now the Poet arrived at the inn, finding the inn to be much like the place, years ago, where he had spoken to the jug-faced man and heard that man’s story. It had also been spring, then, with the river loud through the willows, and he had been traveling. So now he could think of nothing but the story that man had told him that night. And because he could think of nothing else, he would tell us that story. The Poet did not remember the man’s name.

“‘Some men,’ he said, ‘cannot be separated from their names, and once you know them, you will never forget their name, which is of a piece with them. But some men’s names seem like something they just happen to be carrying at that moment, and could put down at any time.’ Then he laughed at himself, and said, ‘or perhaps I have just forgotten.’ And he began his tale:”

The Slave Raider

“The inn, which as I said was much like this one, was forty days by horse from here. It is gone now. The city of which it was a part was attacked by a tribe from the East and razed to the ground twenty years ago, and many people were killed there. I passed by the place once, a decade ago, and would not have recognized it, except for the trees: the mud bricks of the building were melting into the earth, and someone had made a sheep pen of what was left, building a fence of thorn to close the gaps in the ruined walls. But the first time I saw it, it was much like this place.

“A building made of mud bricks seems to live for those who care for it: once the people it lives for are gone, the building quickly melts away, even if none come to destroy it. In this way, a mud brick building has more decency than a building of fired brick or stone. When stone buildings are abandoned and the men who built them move on, they haunt the landscape like a human skull lying unburied on the ground. Everyone who passes them must dwell on lost greatness. It is unseemly. Mud brick is more merciful, following us loyally into darkness.

“I had come there tired, and wanting only a bucket of cold water and then sleep, but I found myself invited into a group of men on a platform much like this one, overhanging a loud spring river. The men were eating mutton from a sheep they had slaughtered earlier that day and had the owner of the inn boil in a large kazan. They pushed mutton on me, though I was not hungry. They were from the desert to the north, and some did not speak our language well. But the man with the face like a jug spoke very well – even beautifully. He was their leader, that was clear –but he was not entirely of their people. He had been about to tell a story, he said, and was glad I had come to hear it. It was very much as if the man had been waiting for me to arrive. He knew everyone else there, and this was a story he wanted to tell to a stranger, so he was glad one had come.

“So, in a way, I was his only audience. And I will warn you – the story he told was fantastic, but without jinn or peri. And perhaps that was what made it so unsettling to me: it was a story entirely of our world, and it was not possible, according to the things we know. Except that it was true. Before he began the story, he held his hands out with his palms to the sky and said a prayer, asking Allah to witness to the truth of what he was about to tell. Then he began:”

The Wanderer

“There were fifteen of us. We were on horseback, not more than a week’s ride from our pasturelands in the foothills. We came upon the trail of a caravan, there in the desert where it just begins to become fit to live in. We tracked the prints of their camels and their men for some time, and so we knew their numbers well. For a few nights we sent scouts to watch them at camp around their sauxal fires. We knew that they had no women with them, and that they were twelve or perhaps thirteen in number. But of course, one does not know what a man is made of until one faces him.

We fell upon them at dawn, with much ululation and waving of swords. Sometimes that is enough, if you catch men when they are not ready for a fight, at their toilet or breakfast. A brave man can often be a coward, when his mind is not prepared. But not these: they fought hard, and there was screaming of camels and horses and men. By the time we were finished, two of us were dead, along with eight of them. Three more of them had run into the desert, where in anger our men ran them down and murdered them.

“The last of them had been knocked unconscious with a clumsy blow from my lieutenant’s sword. This was a lucky accident for him: there is little limit to a man’s rage, and I have shot arrows into a fleeing man’s back, but few among us will kill a man who is already on the ground, senseless. So he was bound with rope, and put into a tent. So much the worse for him, we thought – he went to sleep a free man and would wake up a slave. This was perhaps another reason we did not kill him: to be a slave, we thought, was a worse fate.

“And so, what is sometimes easy had been made very hard. We had to bury the dead – ours and theirs – and of course, we had to see what we had taken. We stayed there that day, putting our dead in the sand separately, with prayers and lamentation, and their dead together in a heap, with no words for them but curses.

They had been carrying gold, in sticks and in coins, a small walnut wood chest filled with Byzantine electrum coins, and also salt in strange cones the length of a man’s arm, of a pinkish kind none of us had seen before. They had saffron, and several bolts of good silk. A good haul, but not worth the butchery and waste. They must have wanted very badly to remain free men, and so had died defending their freedom.

“It was evening by the time I went in to the last of them, where we had bound him in the tent. I half expected him to be dead when I went in: the blow to his head had been from the flat of my lieutenant’s sword, but still his scalp had been cut, and there had been a good amount of blood. He was not dead. He was sitting up cross-legged with his tied hands behind his back, like a man sat down to dinner. Outside the tent, I could hear my men getting into the wine the dead men had carried. My men had been afraid that day, and cruel, and they did not want to remember it.

“The man’s face had some blood on it, and more was in the scalp of his black hair. Perhaps the blood loss had made him paler than he was, but anyway I could see that he was pale to begin with – paler of skin than us, and with light colored eyes: the kind that are called blue, but really are of almost no color. He had been wearing the conical traveling hat of the Hellenes, so I took him for a Hellene or a Roman, who can be among the caravans, and bring a good price—especially if they are learned in languages and writing of them. He looked to be in his thirties – anyway, in the prime of his life – but he had a terrible scar along one side of his face, perhaps from a lash or a flail that had just missed the eye, and had carried away a piece of the edge of the brow. And when we had bound his hands, we had noticed he was missing the small finger of his right hand, and the first knuckle of the ring finger next to it. He looked at me calmly as I came into the tent and sat down across from him.

“‘My men want to kill you,’ I said, ‘and perhaps they will come and kill you anyway. But I think we will sell you instead, though after some time you may wish we had killed you. It depends. Some take to slavery. Others do not.’

“I had thought that he would not understand me. I had spoken to him in our own people’s language, doing it to frighten him, but he replied in our language to me:

“‘I would like to buy my freedom if I can,’

“‘And what would you buy it with, when we have taken everything from you already?’

“‘A story. It is all that I have to pay with. But it is a true story, and perhaps one of the strangest in the world. It is a story you can carry with you for all your life, and as we all know, such a thing is greater in value than any gold or slaves. If you are pleased with the story, I ask that you let me go. That you give me ten of the electrum coins you have taken – which were mine but are now yours – a camel, and a leather case of scrolls which you have also taken, but which are written in a tongue that is not yours, and are of no value to you or to anyone but myself.’

“It was a strange request – the kind one finds only in stories. And for this reason, it was interesting to me. Sometimes I think we find interesting only the things that are in stories. Our real lives and all that truly exists in the world we find very dull. And so I said, ‘If I find your story as pleasing as you say, I will let you go. This intrigues me. It is like the story of the virgin Sanaz, who kept the giant that had dragged her to his cave from killing her for forty nights and a night, telling him many tales. But in the end, she slashed his throat with a sharpened bone while he slept. I hope this will not be my fate.’ And I smiled at this, because of course his hands were tied, and he was hurt and unarmed. And while people like that are dangerous in a child’s story, I had found that they were not so in life.

“He smiled weakly at me. ‘I will do your person no harm. Shall I begin my story now?’

“‘A moment.’

I went outside. The sun was behind the mountains, and everything was losing color except the brightness of the fire my men had lit. Among them were many cousins of mine, and a younger brother. They had put up their tents. And they had put up mine, away from the others and higher up, on a hill of sand, as was fitting to me as leader. They gestured to me to come and eat with them: they had found good smoked meats with the caravan. I took a leg of meat from them, and a water bag, and said I would speak to the prisoner more – to understand who he was, and how much of a price we might get for him, because he seemed an educated man.

“‘Unless we knocked his education from his head this morning,’ my brother said, and they all laughed. I could hear in their laughter that they were already on their way to being drunk, and would sleep well that night.

“I gave our prisoner meat from my own hand, and water. He thanked me, and then he began. I interrupted him some few times with my interjections and my questions, but I do not include those here, as they are of no consequence.”

The Wanderer’s Tale

“You meet me here in the desert, where you have killed my companions. They were not men who were close to me. I was simply moving with them for safety. As you can see from their clothing, they were of the countries near to here, while I am not. And yet I know the languages of these countries very well, for I have lived a lifetime in them.

“But before this lifetime, I was in Constantinople, where I lived longer, and before that in Trebizond, for perhaps even longer. Before Trebizond, I was in Bactria for a time. Before that, Macedon. I think that I come from beyond Greece, from an island where there are Hellenes to the west. I cannot say for certain. It is possible that I come from further, or from closer. I think I am a Hellene, but it is possible that I am older even than the Greeks.

“Do you remember your own birth? Of course you do not. I think no man does, though some may insist they do. But you know – or at least believe – that you were born near enough this place, because soon after your birth, you begin to remember the things that are happening to you, and from your reasoning powers, you later form a picture of your childhood, even though there is much of it you cannot remember. You trust that the people who say they are your parents are your parents, because they say that they are, and they are in your earliest memories.

“Some of your memories last a long time – especially the ones that are unusual. That is the way it is with me. But I have lived so long that much of what I have known, I have forgotten. I remember Constantinople, though if it were not for my scrolls I would not recall how I came there, and of Trebizond I am even less certain: I do not know what I truly remember from that place, and what I have only read in my scrolls, thinking afterward that I remember it.

“I have thought long on what memory is, and I do not think it is what we believe. Sometimes we remember things from outside ourselves: we watch our past selves doing things. And so that must not be memory, but something else – like a story we have told ourselves for a long time, or perhaps a story that others have told to us. The further back I go, the more it is like that. At some point in Trebizond, where my scrolls begin with the phrase ‘I have lived now for at least five hundred years, and have not grown old, though I wait for it’ my own memories fade into darkness. I only know that I am not from Macedon because sometimes I mention in my scrolls having lived in Corinth, and before that in a city called Egosthena. I do not know where that city of Egosthena is or may have been, and I do not know if I am from there, or further. The person who wrote these things, though I know him to be myself, is a stranger to me. Even the handwriting of the scrolls has changed, over the years.

“In the scroll, an earlier set of scrolls is mentioned. These were destroyed at the same time that I lost my fingers. I know of this destruction only because it is written in the scrolls. Even something as terrible as this destruction, I do not remember. I know only that it was in Macedon. There was fighting in the city, and I fled it, losing everything. This was written when I must still have remembered it quite clearly. And so now, speaking to you, I form a memory of fire in a foreign place, and of pain and my bloody hand. And it seems real, except that I am looking down on myself from above, as if I were a bird. I see myself running. I see the top of my head. And I do not see details of other people, or of the city. I think, then, this memory is something created in me from my reading the scrolls. I do not see the other people or the city clearly because my mind has created them, the way the faces of strangers in a dream are made, blurred and indistinct.

“All the time which is my own – the time that I can recall with little error – I have had eight and a half fingers and this scar on my face, which I also received I know not where.

“I must have begun moving early, and moved a great deal. I know this, because I know that I cannot stay in one circle of friends for long. They age, and I do not. Eventually, they grow suspicious of me, even hateful, and in Trebizond a man who had been my friend for many years tried to kill me because my changelessness made him angry and afraid. I think it was really his own death he wanted to kill. I have learned that if you stay young while around you others grow old, you become hated by them.

“I have learned many things that might be of interest to you. I know, for example, that there is nothing permanent inside a man. I have been a great hero at times, and unafraid of death. And I have been a terrible coward, so used to the habit of living that I would not give it up for anything. I have been horribly cruel, murdering a man in cold blood, leaving women pregnant with my children and alone while I rode away from a town not looking back. I have been a fiercely loyal lover, staying with a woman until she died of old age, loving her even when she was bent and withered to nothing. These changes in me do not happen quickly: at all times I have felt that I am one and the same person. I am always the person that I was yesterday, and much of the time I am the man I was a decade ago, or two decades ago. But am I who I was a hundred years ago? I read my scroll, and this man seems different from me. His opinions are not my own, and the things he holds dear are not my own. Is he, then, myself? Most men’s lives are short, and so they do not have time to change much, but I have seen that even mortal men are not the same through their short lives. They are only the stories that they tell themselves, and that others tell of them. That is all. These stories are what gives their life shape, and they are all that we are. What we pass along to others is what lives of us, when we are gone.

“And I have come to understand the gods. I do not speak of Allah, his name be praised, but of the old gods of Greece and elsewhere. Often you wonder how they can be the way that they are in the mythos: indifferent sometimes to human suffering, and at other times so deeply in love. Liars with no remorse or defenders of the truth, loving husbands or philanderers. Jealous or indifferent. Their behavior seems without explanation. But I see now that it makes much sense: sometimes I look at the short lives of the people around me and I feel only contempt for them. How can they delude themselves into thinking the things they do matter? What can they possibly accomplish in their time here, when I have done so little with so much more time? At other times, I am jealous of them – they live with a passion, pouring a quantity of feeling into a single day that sometimes I do not feel for a decade. Death gives their short lives meaning: without it, there is great boredom to this small place in which we live. And together, humans create wonders in their short lives–wonders that other humans destroy, only to create more and greater wonders.

“So I understand the gods: they are immortal, but they are not unchanging. They love humans sometimes, and hate them, and these two feelings are bound together. Sometimes, they look up to humans, and are jealous of them, because death is an engine that makes humans great. But at other times, humans seem like ants to them, valueless because they are here for such a short time, unworthy of promises or kindness, to be swept aside if they bring irritation or inconvenience. The gods are immortal, not unchanging: the Zeus of one story is not the same man as the Zeus of another story. He has transformed with time, growing better or worse, and he will change again. The Cretans say that Zeus is born every year in the same dark cave, in fire and blood – and that every year he dies there. The Cretans are famous liars, but there is some truth hidden in this. For do we ever see the same Zeus, one year to another?

The Slave Raider

“And as I listened to him speak, and looked closely at his face, and at his eyes, I knew that the tale he was telling me was true. He did not look like a young man – not that he looked old. He looked like something it is very difficult to describe: something that has lived a very, very long time without aging visibly or growing much weathered: something not entirely of our flesh – alien to it, because what makes us all the same is our mortality.

“‘But you can be killed.’ I said. “‘With sword or disease.’

“He nodded. ‘I can be hurt or killed like any other man. And surely someday I will go to my death along with everyone else. Perhaps right now, if you wish it. But I do not grow old. And I do not know why.’

“I rose then. It is difficult to describe how I felt. My heart was racing. Part of me wanted to scream at him that he was a liar. Part of me wanted to strike him down. I could feel my hand aching to do it. But another part of me wanted to untie him, and let him go. More than any of those things, I wanted to be away from him. I turned to go.

“‘And what of our bargain,’ he said. ‘What is your decision?’

“‘I have not decided,’” I said. ‘I will come to a decision in the morning.’

“And without turning back, I left him there.

“A wind had come up, coming cold down from the mountains and blowing sand against everything in a hiss. My men were still by the fire, very drunk now, so that they had become quiet, mumbling to one another, arms around one another, their faces drooping and ugly in the shadow and the flame. I found the scrolls of which he spoke, in a leather case on one of the camels. They told me very little, because I could not read them. I could see that they were written in the Hellene language, or at least in that alphabet. I opened several of them. Indeed, you could see that over time the writing changed: or more specifically, it changed, then sometimes returned to some earlier form, then changed still further. I left the scrolls where they were.

“I returned to my tent. I lay in my tent, listening to the grumbling of camels in the storm, and thinking many things. At midnight, with the wind still hissing along the ground, I wanted to kill him. By dawn, I had slept a few hours, and come to the decision that we would let him go. Who was I to destroy such a wondrous creation of God? But before I let him go, I would have him tell me more of his wondrous story. Truly, it was worth more than all gold and slaves.

“They were all dead. To this day, I do not know how he did it. It must have taken time, and patience, and a courage and a terrible coldness beyond anything I can conceive. He must have had some very sharp weapon hidden on him. Whatever it was, he used it to cut the cords that bound his wrists. Then he went from tent to tent, and cut their throats where they lay sleeping. He cut them deep and carefully, to the bone and the whole length of the jaw. Twelve men, one by one. Then he drove off the horses and the camels, except for our fastest horse, which he took for himself. He took what he could carry with him – the Byzantine coins, the gold, and of course the scrolls. I found a horse only after many hours of searching. Because he had driven off the animals, there were tracks everywhere – leaving nothing clear to follow. Slowly, over the next days, I buried our dead and found most of the horses and many of the camels, including much of the merchandise. I wept many times, alone there in that place. And I returned to our home encampment in shame, having led my men, including my cousins and my brother, to their deaths.

For years I cursed my arrogance. It takes cleverness for a man to live his seventy years upon the earth. One must be a man of many twists and turns just to live happy for our short time. One must be clever, and sometimes ruthless. But how much more clever, more ruthless must one be to live dozen times hat long, or longer? I go back to that night again and again, searching for some sign that he was so deadly. And I see nothing. I never was his equal, but thought myself his better. And for that, my companions paid with their lives.

The Great Poet

“And then the Slave Raider raised his palms up again to the sky. It was night now, and the moths clattered quietly against the lanterns hung in the trees. ‘That was fifteen years ago to this day. And I pray to Allah that I will never meet him in this world. Because if I meet him I will destroy him. And it will be a great sin. Sometimes I see someone and think they are him. I try not to look too hard. I try not to look, though I cannot stop looking.’

“After he had finished, the men got up to bed down for the night – not all at once, but slowly. I found myself alone with the Slave Raider. As I stood up to take my leave from him, he clasped my hand and said: ‘Thank you for listening to my story. I swear to you that every word is the truth. Do not forget me.’

“And then I did a strange thing. When I arrived I had been very tired, and I had not even wanted to join that group of men. But now I got on my horse, and I rode away from that place. I rode all night, not even wanting to sleep, and I did not rest until the next day, when I dozed away the afternoon far down the river.”

Batyr

“And as if on cue, the men began to disperse. And I found that I was the last person there, with just the Great Poet. His assistant had gone to see some of the others off. And the Great Poet took my hand in his, and looked me in the eye and said: ‘Good night, Batyr. Travel safe. And thank you for listening to my story. I swear to you that every word is the truth. Do not forget me.’”

Batyr had come to the end of his tale. His heart was beating hard. He had caught himself up in his own tale, and felt himself there again, parting from the Great Poet under the lanterns, with the shadows of willow-branches and moths shivering all around them.

Leila, having long ago laid waste to all the dried mulberries in the bowl and drunk all of the milk, took his face in both of her hands, forcing him to look into her eyes, and grinned at him. “My love, what outrageous lies you men tell one another. And what children you all are to believe them! Blow out the lamps.”

And the courtyard gates were locked all the next day.