|

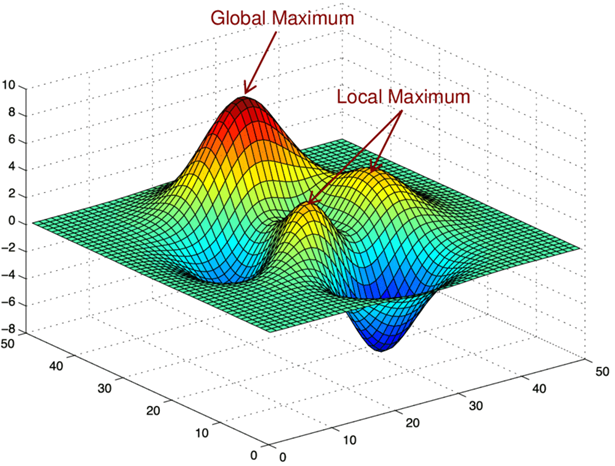

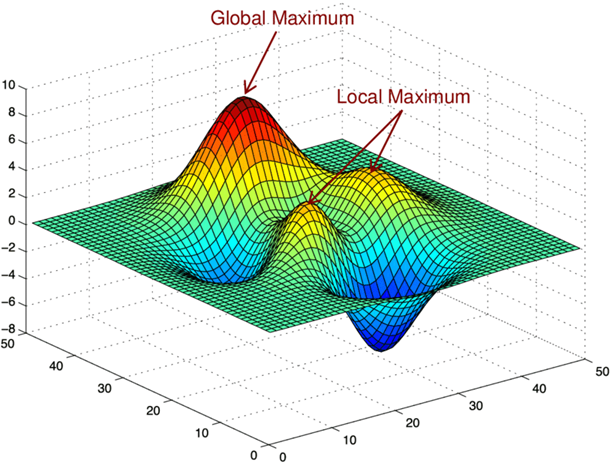

RN: Wole, first of all, I want to tell you how much I enjoyed “An Arc of Electric Skin” – this is a story rich with so many of the elements that make SF such a powerful genre for exploring our condition, and it’s a pleasure to explore it here on Better Dreaming. I think this discussion will also make for a fitting end to this series of explorations of science fiction. So thank you for being the last – the ultimate – conversation in the Better Dreaming series. Reading this story, and considering how to approach it for Better Dreaming, I thought of Samuel Delany’s famous example of how science fiction differs from mainstream (or as he termed it, “mundane” fiction. I’ll quote him here: "'Then her world exploded.' If you say that in a piece of naturalistic fiction, then it's a metaphor for the emotional state of one of the female characters. However, if say that in a piece of science fiction, it might actually mean that a planet, belonging to a woman, blew up." The takeaway for me here was always that science fiction provides a space for metaphors that could not otherwise be used, and also provides a space for the literalization of metaphors, and for the literalization of emotional states. A “wider range of possible meanings” as Delany puts it. And before we continue, I’ll remind readers that there will be spoilers: Better Dreaming talks about entire stories, not parts of stories. The literalization of a state that is both emotional and political is very much an element of “An Arc of Electric Skin”, as I read it. This is a story about a man who gains the ability, through the altering of his skin’s structure, to harness and direct electricity with great violence to destroy a political system that has become unbearable. In an excellent line Akachi Nwosu says: “This country happens to all of us . . . some of us more than others.” Can you tell us a bit about how you think science fiction and its affordances allowed you to tell this kind of tale so effectively? WT: Thank you very much, Ray. I’m glad you enjoyed the story and that it’s the subject of the ultimate story on Better Dreaming. I’ve really enjoyed reading and learning from your deep dives into stories through talking with other authors and I hope there will be more, and perhaps better Better Dreaming to come at some point in the future. Yes, the core of this story is about the literalization of emotional and political states the use of skin as metaphor. To quote from it: “He endured… all of this under the blistering heat of the Lagos sun, increasing his already-high melanin levels, his darkening another physical marker of his endurance. And still, he persisted…” I think that is because that’s exactly how the story came to me. I’d read an interesting paper in the Frontiers in Chemistry journal about the use of heat treatment to increase the conductivity of melanin, which I found fascinating and given that melanin (or eumelanin) is a chemical component of skin, I wondered if there would ever be a way to apply the process to the melanin in human skin, assuming someone could even survive it. I just knew that even if it was theoretically possible, it would have to be painful. And then in October 2020, millions of young Nigerians took to the streets and the internet to protest. The #EndSARS movement quickly blew up but on 20 October, the government sent the army to a protest site at the Lekki tollgate where they opened fire and killed several people. Being Nigerian involves a lot of needless pain, much of which leaves you feeling angry and helpless. I’ve felt that way off and on for a long time since I was a teenager and despite being out of the country, this story, reminded me of all that. And so, this story of Akachi being willing to endure a great amount of pain to gain power to strike back against a government determined to crush its own people came to me. The story in a sense is a literalization of what I knew was the emotional state of many of my fellow Nigerians on the ground back home and I wrote it mostly for them. Science fiction is unique in being a framework that allowed me to do this because of its nature as being both removed from clearly defined reality while simultaneously allowing deeper immersion in a specific aspect of the human experience. As the excellent guidelines for submissions to Asimov’s (where this story first appeared) say: “… consider that all fiction is written to examine or illuminate some aspect of human existence, but that in science fiction the backdrop you work against is the size of the Universe.” This capacity for “removal” from reality, I think, allows the author (and the reader) a certain distance and perspective from exaggeration that can make things more universal, while still retaining enough specificity for the core theme or emotion or philosophical idea to resonate deeply. I think of it as a kind of thought experiment or a mathematical transform. Sometimes an equation is too complex (or cumbersome) to solve in a standard way, but by applying a transform, manipulating it in such a way that some key feature or variable is emphasized, more clearly/simply defined, then it makes it easier to solve. I think of science fiction as being a set of transforms for character and theme elements, for literalizing them. I think if I’d written a similar story about a political action in Nigeria, it might be too personal and painful for me to work through, or for others, or it might not be as impactful, or it might be taken as a kind of propaganda or get lost in the weeds about specific details and historical accuracy when what matters is the feeling and in a sense, directly connecting that feeling of pain and powerlessness and all its varied history, to the power that we possess to change things, difficult as that may be. RN: My second question will be simple, but I have a feeling your answer will not be: why electricity? WT: Surprise! My answer is simple, I think. Its because of the paper linking melanin and conductivity which I mentioned earlier. The ability to control electricity is a common superhero power archetype and this story also plays with the superhero story form. So, conductivity (and consequently the ability to manipulate electricity) lent itself quite smoothly to the idea someone looking for the power to change a system, to longer feel helpless. I did become a bit hand-wavy with the science of how manipulating electricity would actually work but I was more focused on the theme and emotion than going for 100% scientific accuracy. Besides, there is a long tradition of science fiction-adjacent origin stories for superheroes that don’t really hold up to scrutiny. Gamma rays? Lightning? Radioactive Spiders? Sure. Why not add my bio-annealing to the list. Besides, electricity also harkens a bit to the common Nigerian saying “thunder fire you” which implies that lightning (or thunder as we say) would strike down those who did evil as divine retribution, so that was a fun association. RN: I definitely came away with the sense of a superhero origin story but saturated in the realities of place and time and political structure. And I’d like to dig a bit deeper into what you say above about playing with the superhero form. It seems to be a trend recently to make attempts to turn or deepen the superhero mythos. It’s not particularly new – Watchmen was 1986, and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns graphic novel by Frank Miller was definitely an early precursor of the general trend. The Dark Knight novel was over 35 years ago now (can that be true?) but certainly The Boys and Invincible are just two current examples of how this tendency to add grit, and to question the motives and the legitimacy of superheroes, has become a new trope. But while there’s been a lot done to add nuance, the setting hasn’t altered that much: if the stories don’t take place in the United States, they take place in a world that is depicted from the POV of the United States, with few exceptions: versions of Europe, the Middle East, East Asia, and Africa remain very much American (Hollywood) versions of those places that people who have spent any time living in them would find laughable. Here you truly move the superhero setting to a new context, and that brings the story real strength. I personally, as someone who has spent almost half my life outside of the U.S., am hoping for a future for Science Fiction that will be truly global – though we are not nearly there yet. What do you think has to be changed in the way SF is not to make this global future a reality? WT: Yes. I absolutely love the deepening and deconstruction of superheroes because it takes these simplified ideals and attempts to engage with what they really mean and why we are drawn to them. About the “Hollywood” version of places in superhero cinema, I cringe every time the MCU mentions Lagos (where a key incident during Captain America: Civil War takes place). Not only are the depictions of the place and people largely inaccurate, but they also don’t even pronounce the name of the city correctly. I think it goes to show how the place is used as little more than a veneer for diversity, to create the image of ‘globality’, without actually engaging with the place or the people. I was recently on a virtual panel at the 2022 Worldcon called “The Future of Science Fiction Is International” and we talked quite a bit about making SF truly global. I’ll start by saying that making SF global isn’t just about “diversity” or “representation” at a surface level to make people feel good, even though that itself is already a very worthwhile goal (and a natural result). I’d argue that making SF more global is about making SF itself fundamentally better because speculative fiction, especially science fiction as we noted earlier, is a genre of ideas, of concepts, of ways of looking at the world and of being human, so the more of that we are aware of and consider in SF - the more views, philosophies, scientific approaches, religions and cultures, etc. – the more variations of ways of being human that we can factor into our considerations, our stories and our projections about the future of humanity. Producing and reading global science fiction helps us understand ourselves and each other better, it helps us build a better empathy, gives us a broader palette of root ideas to apply to our visions of the future rather than focusing on one dominant hegemonic thought framework. So, anyone that cares about the soul of science fiction should care about its global diversity. To use another mathematics analogy: if you start from only one point or one approach to iteratively solve a complex problem and focus only on it, you can get trapped in what’s called a “local optimum” - where you make progress up to a point and once you ‘peak’, you think that’s the best solution simply because you aren’t aware of the complete problem space or of other starting points and approaches. To arrive at a true ‘global optimum’ (if one exists) usually requires many different starting points, and sometimes different approaches. WT: So how do we get toward a global optimum Science Fiction? I’m not sure but I think there are 3 angles to come at it from simultaneously:

Production: The first step I think is recognizing that people of every society have hopes, fears and dreams about the future, about different ways of being human. And many of them write about it. Or at least would if they could. But not everyone everywhere has the resources, infrastructure and industry in place to do so, or to even reach a local, not to speak of the wider global SF audience. This is at its heart a socio-economic issue, but collaborations can help us trend in the right direction. So for those of us who have access to more resources can reach out and suport local production and translation of SF. For example, the great work that Neil Clarke is doing at Clarkesworld, the consistently excellent work of the folks at Strange Horizons as well as Francesco Verso with Future Fiction. Content: The second and easiest one, I think, is to create better, more global stories. To clarify, I don’t think having global science fiction means that every story should try to include every culture and country and thought and viewpoint and blend them into some weird, thin, homogenous soup. That will probably lead to bad stories that no one wants, not even the authors. Instead, I think we should aim to have a broad body of science fiction that comes from as many places as possible (related to the point above), which while being composed of individual, culturally attuned stories, maintains an awareness of the wider world and its variety of viewpoints/experiences on the core theme of what the story is exploring so that where the story intersects with those other places/people/cultures, it can do so meaningfully, even if briefly. Those are the types of stories that all of us can try to start writing today. For example, Kim Stanley Robinsons The Ministry For The Future is a novel about climate change – a global issue and in it, he shows a keen awareness of the variety of peoples from everywhere in the world and their possible responses to it, while still keeping the story focused on his two main “Western” characters. Reception/Community: This is related more to how works are received after the fact, once they are out in the world. The way we think about what is worthy of recognition and remembrance. For example, Suyi Davies Okungbowa on that panel said something to the effect of: a truly global SFF canon will have multiple entry and exit points or multiple references/touch points for the same things/tropes. I love this as it’s a way to thinking of canon that recognizes that depending on where you’re from you may have come to the same point via different roads or resonated with a different works along the way. So if someone asks for a classic SF “first contact” story, instead of only and always mentioning H.G. Well’s War of the Worlds, we make efforts to also mention Jean-Louis Njemba Medou’s Nnanga Kon, or Lao She’s Cat Country or similar stories. A lot of this can be addressed by reading, critiqing, researching and nominating for awards widely as well as ensuring that when we talk of global science fiction events and community, we try to include as much of the actual world as possible (I’ll note here that Worldcon has been improving at this recently and I hope that continues.) RN: I love this statement you made above: “I think of it as a kind of thought experiment or a mathematical transform. Sometimes an equation is too complex to solve in a certain way but by applying a transform, manipulating it in such a way that some feature or variable is emphasized, more clearly seen, then it makes it easier to solve. I think of science fiction as being a set of transforms for character and them elements, for literalizing them.” It’s a great metaphor for how SF works. Can you talk about how you became drawn to writing science fiction in the first place – your specific pathway into the genre? Was it where you started as a writer, or something you came to later? And why? WT: Thanks Ray. I like mathematical metaphors a lot, as you can probably tell. I suppose one could say I was genetically predisposed to be a science fiction writer because my mother studied English literature and my father studied engineering. It’s a joke I’ve made before. But I think it’s at least partially true because I became drawn to science fiction by reading my parents books when I was very young. I read a lot. Read my dad’s entire encyclopedia collection from A to Z even though I didn’t understand most of it. I read Cyprian Ekwensi and Florence Nwapa. Even Enid Blyton. I remember reading Isaac Asimov’s Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, which charted the history of science from ancient to modern times with short biographies of everyone in it and he tried to make it global, as he could anyway, including some historical Arab and Chinese natural philosophers, etc. And the biographies were wildly entertaining. That had an influence on me. I really enjoyed seeing science and technology not only as topics to study but as things linked to stories of real, relatable people. I was always a reader and eventually, in my teens I started trying to write too. I just liked stories. I didn’t take writing seriously till about 2009 or so though. And while I started out writing all sorts of fiction, mostly published in local Nigerian magazines and online blogs, I naturally drifted back to science fiction (and fantasy) since I’ve always enjoyed those kinds of stories the most. I’ve discussed a bit more of my writing journey in detail in an interview with Geoff Ryman over at Strange Horizons if you or your readers want to know more but that’s the big overview. RN: I love what you say above: “Producing and reading global science fiction helps us understand ourselves and each other better, it helps us build a better empathy, gives us a broader palette of root ideas to apply to our visions of the future rather than focusing on one dominant hegemonic thought framework.” – having lived nearly two decades outside of the United States, I have been struck by how every year it seems more and more local culture is drowned in the slurry of global monoculture. English has become much more of a Lingua Franca than Latin (or certainly the Sabir pidgin, to which the term Lingua Franca actually refers) ever was, and if folk music is passed down from one generation to another these days, it seems it is passed only in the thinnest and most stereotyped of forms, autotuned to death and drowned in imitative studio beats or in a generic pseudo-“Eastern” rhythm. Yet the maintenance of what one might call our “separateness” – the things which make our cultures unique – seems both impossible and, perhaps, not something to be strived for. I worry, at times, that by the time we come to understand one another there will be nothing different left, or only superficial differences left, to understand. Coincidentally, in my real job I have been having conversations with Indigenous people about local ownership and Co-management of parklands, and one of the things they noted is the use of the word “incorporate” as in “Science should learn to incorporate local knowledge into its frameworks.” One of my Indigenous colleagues pointed out that this implies a massive power imbalance, in which science essentially consumes local knowledges (the plural here in intentional) but its own structure does not fundamentally change. I find myself thinking of how rock music in the sixties “incorporated” the sitar and other “Eastern” instrumentation, without fundamentally altering its own DNA. I’ve been pondering this for a while, and trying to come up with a better metaphor for how this relationship should be defined. You outline pathways above – production, content, reception / community – for a more global science fiction. But here is my question: can we keep science fiction from “incorporating” local viewpoints, and instead fundamentally change what it is? And what do you think the best metaphor for the new structure of understanding would be? WT: That’s a great question Ray, a great one. I think we need to go back to the source. “Modern science” as it stands today, took shape in the 19th century, and evolved from natural philosophy before it fully became an empirical framework. So, at its heart science is philosophy. And philosophy is the systematic study of the world. Of existence. Of reality. Every culture has that. However, as you said, I also think that separateness, uniqueness is impossible to maintain. No culture is static anyway. That includes their philosophy. And so, it stands to reason that as cultures and ideas and ways of being encounter each other, they will change, some aspects are lost, modified, improved, and that is inevitable. However, what we would hope is the result of that change is something better than what came before. Something that takes the best elements of both that works for as many people as possible or in appropriate contexts and then moves forward. Which cannot happen when we have a power imbalance as you mentioned. That’s where I think the understanding of science as philosophy can help. I still hear people say things like “Colonization was bad but at least it spread civilization around the world”. And besides the obvious wrongness of that statement, I usually ask them to imagine what the world would be like today if instead of forcibly subjugating and exploiting people they encountered, the colonists had meaningfully engaged with the people and exchanged ideas and understanding of the world equitably. Engaged with the natural philosophies they encountered to move forward together. Imagine what that world could be today if that had been our history. My forthcoming story A Dream of Electric Mothers in the Africa Risen anthology does this. Reimagines an Africa that was never colonized and where local Ifa practices and knowledge has merged with western computer technology to create a different kind of artificial intelligence. But as anyone who’s ever worked in a team can probably attest to, it’s harder and more frustrating to try to truly communicate with people and take everyone’s ideas and thoughts in a balanced way to come up with the best course of action for the team but also far more rewarding when it works. Unfortunately, it’s often easier for the most dominant personality to push their own ideas forward and not let others speak. And while that may get a result faster, its probably not going to be the best result or even a good one but because it keeps getting pushed it seems to be the only way. That’s what I think has been happening for much of human history. Cultures have always been changing but doing so sub-optimally. Sadly, perhaps this is just human nature, that whoever has a perceived power advantage will exploit it. But I choose to believe we can be better than that. I’ve seen enough examples of people coming together with the single objective of finding the best way to resolve an issue to give me faith. So, what can we do as science fiction writers? What I mentioned earlier about production and content and reception of global works is the first step towards establishing a power balance in the field, and hopefully that inspires scientists to seek that balance in their work. At the same time, I think instead of science fiction writers simply reproducing tropes of what “science and technology is” in our fiction, we can try to go back to their core and reimagine the philosophical underpinnings of science and technology before extrapolating them into fiction. Not all the time of course, but enough for it to matter. Imagining a better, different way of science to tell science fiction stories. It’s like alternate history science fiction or even “science fiction of science fiction”. Exciting to think about, isn’t it? RN: It really is, Wole. It really is. And I have a feeling that this is what the best SF is doing, right now. And it is likely the SF of the future. I certainly hope so. I love what you said above about imagining “what the world would be like today if instead of forcibly subjugating and exploiting people they encountered, the colonists had meaningfully engaged with the people and exchanged ideas and understanding of the world equitably. Engaged with the natural philosophies they encountered to move forward together. Imagine what that world could be today if that had been our history.” I think that exercise in uchronia you outline above is an important one. Imagine what we could have been – and could be in the future – if the focus was changed to exchange on equal footing, to cooperation, to open dialogue and learning. What a fitting place to leave this conversation, Wole – and a fitting place to end this cycle of Better Dreaming conversations, of which this is the last for now. It has truly been a joy, and a deeply affecting learning experience, for me to be a part of this. I thank you, Wole, for taking the time to be a part of it as well. I’ve learned a lot from our conversation. WT: And thank you Ray, for the wonderful questions. I really do enjoy deep engagements like this with science fiction work (mine and that of others) so this has been a lot of fun. I’ve learned a lot from your questions, and from Better Dreaming overall. I look forward to learning a lot from the Mountain in the Sea as well. Good luck with the novel. So long (for now), and thanks for all the fish.

1 Comment

RN: First of all, Maria, thank you so much for agreeing to do this with me: these Better Dreaming conversations demand a real time commitment, and I want you to know I appreciate it. And thank you for choosing “Deepster Punks” as the story you want to talk about. There’s so much here to work with. I really enjoyed this story, which I think in some ways combines the best of the “old” science fiction and the “new” science fiction in one package. But I’ll return to that later (and deconstruct that false binary.)

This happens to be the first time I’ve discussed a story from an anthology for Better Dreaming. Can you start off by telling me a little about that? Strangely enough, I’ve also never submitted a story to an anthology call before. Did you have the story written already, or did you write it for A Punk Rock Future? How did all of this play out? MH: I had been working on what was to become this story for a while before I submitted it to the A Punk Rock Future anthology, but I could never quite get a handle on how to tell it the way I wanted to tell it. I’d done several different rewrites but was never quite happy with any of them. Then, I saw the anthology call, and I immediately felt that my story could be a perfect fit, and that helped me focus and re-write the story one final time. Splitting up the timeline and going back and forth between past and present was one of the things I did in that final rewrite. The reasons why I felt this story would be a good fit for A Punk Rock Future are not easy to put into words. It’s not a story about punk rock or even music, but the main characters as I saw them in my head, had a definite punk rock vibe to them, and their music choices were always part of the story itself. I think that was also one of the things that the anthology call triggered for me, creatively: thinking about the characters as people who would be listening to punk rock while they worked and who would love to find and listen to the best and rawest tracks they could. I’ll always be hugely grateful for that anthology call for the way it crystallized the story in my head and provided the spark I needed to get things right. RN: One of the things I love about this story is how it focuses on skilled “blue-collar” labor. I like this line in particular: "’You might have sold your bodies to the Company, and you might let them ship you from sea to sea, but they won't really take care of you. No one cares about us deepster punks, except other deepster punks. That's why we have to look out for each other. On every world. On every station. On every shift.’" I am reminded of the kinds of positive, skilled “blue-collar” loyalties that Susan Faludi writes about in Stiffed. I am also, though, reminded of past blue-collar jobs I’ve held where there is the sense of working together not for but rather despite the “Company.” And no matter what company it is, it’s always “the Company.” There’s always an awareness that the people we work for don’t have our best interests at heart – so we had better look out for one another. Can you talk a bit about this element of “DeepsterPunks”? MH: That kind of blue-collar solidarity was absolutely one of the main things I wanted this story to be about right from the start. It’s one of the things I love about Ridley Scott’s Alien: that feeling of a group of people who are doing their jobs and who depend on each other and each other’s skills, while they’re in the “belly of the beast”. The beast in this case being both the company, and the system that puts the company in charge of their lives. I’ve always gravitated toward these kinds of stories and fictional worlds: stories about regular working people, whether the genre is fantasy or horror or science fiction. More specifically, one original inspiration for this story was a Swedish radio documentary about the deep-sea divers that helped Norway establish their oil fields in the North Sea (Vice covers some of that history in this article: https://www.vice.com/en/article/av4n5z/poineer-norway-north-sea-divers-skjoldbjrg-876). The story about what those divers went through, what they were put through by both the companies employing them and the Norwegian government, is gut wrenching. They were paid pretty well, and many of them were young and eager for glory and adventure and likely didn’t mind some danger when they were recruited. They were good at what they did and a lot of them loved living on the edge and being lauded for their skills and their toughness (both mental and physical). At the time, those divers were doing things no one had done before: diving deeper and in colder water, for longer, under extreme and unprecedented circumstances. Many of them died, many of them were damaged for life by what they went through. Things were done to them, and they were made to do things, that were totally experimental and put their lives at risk. Their work was crucial in establishing the tremendously profitable Norwegian oil industry, and even though they were paid well, the higher-ups showed little regard for their lives. In the documentary I listened to, several of the old divers talked about how they came to value their relationships with each other, with the other divers, above all else. They were often sent down in pairs to do their work, and one guy would stay in the dive bell while the other headed out to do whatever work had to be done on the sea floor. If anything went awry on the surface or below, the guy in the dive bell could choose to signal the crew up top that he needed to be brought up before the second guy had time to come back, essentially abandoning and killing his co-worker. He could also choose to wait for the other diver to come back so that they could both be brought to safety together. One comment one of the divers made was that you came to value the co-workers you knew would wait for you, and be leery of the guys you knew or suspected would not do so. I wanted to capture that feeling in my story, that feeling of us vs. them with the crews vs. the company, but I also wanted to capture how much these workers had to rely on each other, and how important that trust was to them. If you had doubts about a person and how they would act in a difficult situation, that would be a major problem because of the inherently dangerous nature of the work. The reality of what those divers went through is both exhilarating and devastating, and it was on my mind constantly as I wrote this story. I wanted to write about a group, a community of working people who live on the edge of what is physically and technologically possible and who have to rely on each other and their own skills in order to survive, because the company employing them never has their best interests at heart. In general I just really like stories that are told from this kind of perspective. Like I said, it’s one of the things I love about Alien, and also Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. More recently, I’ve seen it captured really well in Suzanne Palmer’s Finder Chronicles. RN: I love the fact that the story is, while science fiction, very much tied to concrete, present-day concerns here on Earth. One of the other things I love is the way the story takes place on Earth. Space is there, informing and enriching the story, but the action is entirely on this planet, and I feel like that rendering of the “space” element as peripheral is also powerful. You get a sense that these are Earth concerns, and not alienated from us. And I did get a strong sense of the influence of Alien here – not only in the gritty, working-stiff element, or in the “Us-vs.-The Company” sense, but also in the way gender is almost a throw-away: Who is male and who is female seems interchangeable, and that interchangeability seems (as it was in the Alien screenplay, though that was slightly marred by later filming decisions) entirely appropriate to this future. How much do you think about the gender of a character when writing a story? How do you perceive your use of gender here in “Deepster Punks”? MH: There are a lot of girls and women in my stories, and that is something that has always been a pretty conscious choice on my part as a writer. I want to write women and girls who are at least as complex and as complicated as the women and girls I know from real life. In all my work I try to stick closely to that: to write people, including women, in a way that captures the many shades of motivations, demons, emotions, strengths, weaknesses, and so on that I see in human beings in the world. In this story in particular, I wanted to write about a relationship that is really intimate which is something I don’t do very much in my fiction. I’ve written a lot more about sibling relationships and friendship than about romantic or sexual relationships, but for Deepster Punks, I really wanted the two main characters to be tied to each other on every level: as friends, as co-workers, as off-again/on-again lovers. And when I tried to imagine what kind of world and workplace Becca and Jacob were part of, I felt that in their work, to them, gender would be largely beside the point. It’s the skills and abilities, and the reliability, of each person that matters, and that’s how they connected to each other originally, and that’s the connection that forms the basis for their friendship and also their physical relationship. They can rely on each other, or they used to be able to rely on each other, anyway. So to answer the question, my default when I’m writing is to write women and girls and try to portray them in all their horror and glory, and never reduce them to some “idea” of what women and girls are “supposed” to be like. In “Deepster Punks”, the challenge I gave myself was to portray a relationship, the attraction and the connection, between these two people and while I knew early on that they would be Becca and Jacob, a woman and a man, their gender was less important to me than what kind of characters, what kind of people, they are. Beyond that, in my head as I wrote this, I sort of imagined the community of Deepster Punks as something of polyamorous community where people would hook up with whoever they worked with, if they liked each other enough, and if they were all so inclined. There are hints of that in the story, though I never went into much detail about it in the text. RN: This is a great line from the story: “The pain sliced through me, so sharp and jagged I had to close my eyes. She'd been the best of us. Our mother-goddess, our patron saint of safety first, and now she was gone.” A lot of this story is also about leadership and mentoring, and the pain of losing not only a friend but also a mentor. Petra, the dead leader being spoken about in the quote above, really leaps from the page. Even though she is dead before the story opens, her presence is absolutely felt. Can you talk a bit about the creation of her character? MH: Petra was absolutely central to this story and some early versions included scenes told from her POV. I wanted her to be older, like solidly into her 60s when she passes away, which is something I feel we always need more of in fiction: older people who are driving forces and have a real strong presence. Even Jacob and Becca are in their 40s-50s in Deepster Punks. I think in a lot of workplaces or other organizations there are leader-types like Petra who are able to shape the culture and working climate in a workplace or a company or an organization, and they can have a real and lasting impact on the people they train and mentor as they pass through the ranks. I felt like Petra was definitely that kind of person, a person who tried to create a tightly knit, caring community inside a predatory system that did not value the workers. And she succeeded, at least to some extent. It was important for me to show that even inside this callous and cruel system ruled by governments and corporations, by greed and profit, there was a sense of community and comradeship, and that this is what made life bearable for the crews. I think humans are capable of treating each other terribly, but we are also capable of compassion and solidarity, and just like in the story, people often create their own communities and ways of helping each other within oppressive systems. Those communities can help people survive, even when those in power, and the political and economic system that underpins those in power, do not really care about the lives or wishes of ordinary people. And I think an important factor to create those kinds of communities, that kind of resistance, is people like Petra who take it upon themselves to teach and guide others and create an atmosphere where compassion and cooperation are valued even if that goes against the official laws and regulations. RN: Above you say: “Petra was absolutely central to this story and some early versions included scenes told from her POV. I wanted her to be older, like solidly into her 60s when she passes away, which is something I feel we always need more of in fiction: older people who are driving forces and have a real strong presence. Even Jacob and Becca are in their 40s-50s in Deepster Punks.” What is really striking to me is how, even as fiction writers themselves grow older, they often continue to write younger characters. My hypothesis would be that this has two general roots: one is the strong North American (since North America continues to dominate these markets) tendency toward valuing youth over age – a tendency that runs counter to other parts of the world. In much of the world, older people are considered wise, or experienced, or seasoned by life. In North America, however, they are often considered obsolete, are condescended to, and are relegated to invisibility. The other root, it seems to me, is the bildungsroman model of fiction – the idea that the core stories we tell are essentially “coming of age” stories. I loved that, in this story, you push against both these molds, presenting middle-aged characters who grow and change. And in a skilled trade where apprenticeship is such a core part of everything, the idea of respect for seniority makes good sense. Do you have models in fiction of older characters that you admire? And can you speak bit about the importance of representing older characters? MH: I think there is a really, really strong bias or trend or whatever you want to call it in fiction, both in books and stories and in movies and TV-shows, that interesting things happen to young people while older people, especially as old as 40-50+ (and even more so if they’re women), are bystanders or minor characters. In one way I understand why: I mean, I did a lot of adventurous things in my younger days I wouldn’t necessarily do now! However, as a writer I want to write older people who are as interesting, and contain all the complexities, as younger characters do because that is the reality I see all around me. It’s also a way to do interesting things with some tropes in genre fiction, to put older characters in situations and stories where the expectation might be that they should be younger. There are some great examples in SFF. Angela Slatter’s Mistress Gideon from her novella Of Sorrow and Such is one of those characters. Slatter’s stories in general are full of fantastic older characters who do terrible and wonderful things. Chrisjen Avasarala from The Expanse is another awesome example of an older character that acts against the common expectations for a character of her age. Both in the show and the books she is one of my favourite characters in science fiction. And one of the reasons I enjoyed Squid Game the show so much was definitely the use of older characters. RN: Above you say “It was important for me to show that even inside this callous and cruel system ruled by governments and corporations, by greed and profit, there was a sense of community and comradeship, and that this is what made life bearable for the crews.” And I immediately think about people I knew when working retail who seemed built to help others “get through it” by making the workplace tolerable. And they are usually a bit older, when I think back on it – maybe not in their 60s, but a little older than those they are working with. It’s as if mentoring – which I think is at the core of Petra’s character – is something built into us – and as if, in a way, it helps us resist, or at least build our resilience to – the system. But it occurs to me too that these mentors also help accommodate us to the system – and here, it is a system that ends up destroying Petra and then Jacob as well. For me what haunts this story is the sense that in the end, although we do everything we can to build compassion and solidarity within the rank-and-file, the indifference of the system tears us apart. Is this a story about resistance, then? Or the futility of resistance? Or something else entirely? MH: Oh, for sure this duality of Petra’s mentorship was on my mind as I wrote the story. Petra taught them to take care of each other and be responsible for each other, but like you say, she also helps the company by making the workers fit themselves into the system instead of abandoning it or rebelling against it. The way I imagined the society Becca and Jacob find themselves in, is that it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to live outside the system and that the Company, and the political system, are so powerful that most people see any kind of rebellion as futile. Also, I think that for the Deepster Punks, they are very much in love with the danger of the work, and with their status as “daredevils” living on the edge. And maybe with the money too to some extent. They are not rebels. They like living on the edge, and they get a kick out of doing dangerous work that a lot of people wouldn’t be able to do, or dare to do. And I think that for Petra, she saw her role as being someone who honed them into a community within the Company, within the system. Under other circumstances, in another story perhaps, she could have been more of a rebel and resistance leader, but here her focus is community and survival. What I wanted to portray in the story is mostly the way people find ways to survive within systems that do not care if they live or die. In my eyes, that is a very common human form of resistance, to care for people around you and to care for yourself, even though you do not rebel or try to overthrow the system. It’s like trying to make safer spaces, more caring and nurturing spaces, inside this behemoth of a system that is not concerned with the welfare of individual people unless it’s for profit somehow. That said, I do wonder what Becca and Jacob would do after the events of this story. Because I do think that they might have been pushed past the limit of what they can tolerate, and I feel like whatever they do next might be something that involves more overt resistance (whether inside or outside the Company), or maybe they would just walk away from the work. It is something I think about. RN: I really like how you explicate above the idea that Petra’s focus is community and survival, and how the story focuses on the way people find ways to survive within systems that do not care if they live or die. Let me ask you: do you find writers to be in a similar system? And do you see, or feel, a sense of community built around a similar idea? Watching the latest court battle over the increasing monopsonist and monopolist tendencies in publishing, it seems as if the industry is at once becoming more consolidated, in the negative sense, and at the same time more fragmented. What do you think about the current state of the community formed around the skilled trade of writing? And specifically (if you want to speak to it) of speculative fiction. MH: Looking at the current news items about the publishing world at large, I’m appalled. To see the top people at these massive publishing houses essentially claim they don’t know how anything works is bad. And the way they discuss earnings and money for writers shows a real disconnect from the reality a lot of writers, in SFF and elsewhere, experience. Hearing the stories about so many editors and other people at publishing houses, in SFF and mainstream lit, quitting because they are not getting the compensation or the respect they deserve is also devastating. It really seems to be that the money generated by the books isn’t going where it should be going in the industry. It’s not going to writers (unless you’re a Big Name), and it’s not going to the editors and editorial assistants who are the main support for writers. There are obviously indie publishers where the dynamics and financial situations are different, but taken all together it makes me wonder about how and why the publishing business are missing so many opportunities to support and nurture new, and old!, writers. As for the speculative fiction writing community, I think it can be a hugely positive force and is often very supportive. There are certainly power structures, and power dynamics, at work that are not always clearly visible or evident unless you have some inside knowledge and that can feel sort of forbidding at times when you’re new… and maybe when you’re not new, too, to be honest. Looking at it on a purely personal, small-scale level the speculative fiction community I interact with means a lot to me. When I first got into writing, I had no community at all. This was a long time ago when I still wrote in Swedish and had a Swedish publisher. My editor at the publishing house Norstedts at the time was great, but he was based in Stockholm and I lived far away from that scene. I didn’t know anyone in my everyday life who was a writer. And since this was before the internet took off, I didn’t have an online community either. I’d meet people at some events, but it was not enough to really get a network or community thing going. When I came back to writing in 2015, after years away from it, I started writing in English and I was also already on Twitter. Now, I know social media has a terrible side, but for me, it has meant that for the first time in my life, I have a community of writers that I know and interact with on an almost daily basis. It’s made a world of difference for me both as a writer and as a person, and it has made me realize how important these kinds of friendships and professional relationships with other writers can be. RN: Maria, that note on having a community of writers for the first time in your life seems like a good one to end on. I’ve also found the SFFH community to be, overall, quite supportive, and this Better Dreaming series has been a wonderful opportunity to connect with people whose work and thinking I admire. Thanks so much for taking part in it. This is a wonderful story, and I feel like we could keep talking about it forever, digging into its layers. But I also think all conversations are just fragments of a larger conversation. I look forward to continuing this one with you at another time, perhaps in person somewhere in the world. MH: Thank you so much for having me! I find that as a writer, I make so many subconscious choices when I’m writing, choices I am aware of, but don’t really think about making. Talking about one of my stories in depth like this is rewarding even for me, because it brings up a lot of those things that goes on beneath the surface of my mind as I’m writing. I’m always a bit nervous to talk about my own work, but this conversation with you was pure joy. Thank you. RN: Ai, thank you so much for agreeing to have this conversation with me. I am excited to talk to you about “Give Me English”, and – having read it several times now -- I think the story will provide us with some excellent topics for conversation.